Interpretation of classical guitar music is what makes the difference between a mechanical rendition vs. a musical one. But what does that mean, Musical?

Musicality is largely an understanding of musical syntax. It allows us to communicate a shared feeling between strangers, even if they are from another culture. It can be learned, and in this post I hope to share five basic rules or guides to help develop your own interpretations.

The inadequacy of notation

It doesn’t take to much digging on the internet to find a heated discussion about TAB vs. notation. To take it one step further I will throw in my own two cents and say that neither of them do a particularly good job of communicating music.

For communicating general rhythm, pitches and a structural overview they suffice. But, once we have tamed the mechanical aspects of a piece, much of the study time is dedicated to musical nuance and gesture. Things like tapering off a phrase, or slightly emphasizing a chord, giving a focus on one voice but not the other, adding vibrato, and letting the music breathe between ideas. All of these interpretational aspects are left up to our own understanding of musical style and syntax, they are generally not included in the score.

You will find, with some more contemporary composers, scores that have an overload of instruction in an effort to communicate exactly what they want, but this is the exception rather than the rule and in the end it can actually hinder the overall learning experience because everything is so micro-managed.

The solution lies in your own understanding of musical interpretation. It is something that is elusive to many people and I would argue that apart from fingering and technique it is one of the major focuses of private lesson time, especially for advanced students.

What I hope to do with this small list is to provide you with some general “guides” to interpretation that will inform your interpretations without needing someone to tell you what to do. They are not written in stone, and should be taken with a grain of salt, as there are always exceptions and varying circumstances.

What I do know, for certain, is that I have repeated these concepts again and again over the years as a teacher and if you can absorb and use these guides, then you will be ahead of the game!

1. Beat-y playing

One of the first ideas we are taught when learning music is to play in time. This involves time signatures. Somewhere in that learning you will be told that the first beat, the down beat is the strongest beat in the measure and it should have a heavier accent compared to the other beats.

As a broad generalization this is true. Accenting beats two and four is also true in jazz. In fact, general accent rules in music work very well for any music that is associated with movement. Swing dance, marching, salsa, polka, the waltz. Dance forms walk hand in hand with accented beats. It is almost like the dancer is using the body as a percussion instrument. The dancer isn’t moving to the band, she is part of the band!

One of several exceptions to this is classical ballet.

My wife is a Swing Dancer, and her foot pats like a drum when she dances. She plays with the beat, stretches it, arrives early late and in the groove, but in general it is safe to say there is a strong and visible link to the beat. When watching classical ballet, however, you might have a hard time seeing the physical link between the dancer’s body and the beats in the music.

A ballet dancer is more concerned with line, phrasing, and form as opposed to synching up with the conductor and individual beats.

I see a correlation between a classical ballet dancer and a classical musician. While there are pieces that we may play which are heavily influenced by folk forms and dances, much of the pure music we play is elastic in nature. It is guided by line, and phrase, and contours of sound.

To do this, we have to abandon the rudimentary idea that we should always accent certain beats in each measure. If we do this all the time, then we break up the long phrases we are trying to carve out, we lose the contour of our sound.

The guitar does some things quite well, and being a plucked instrument, it does a good job of providing rhythms. It can be almost percussive at times. With this as its strength it means that we have to fight quite hard to carve out a long languorous melodic line without breaking it up into chunks or individual beats.

“Beaty” playing is a term that Ben Verdery used when trying to get me to play longer lines in music and the term stuck with me. As a guitarist we can often grab at chords, especially on the downbeat, and unintentionally accent them. This over emphasizes the beat and breaks up melodic lines.

Kind Of Like Acc-en-ting Ev-er-y Syll-a-ble In A Sen-tence, it breaks the flow of phrase and also makes it harder to understand. It might be useful if we want to be a little different or surprising, perhaps in a repeat, but in general it just makes the music break up into chunks and we can’t hear the more important whole.

The first step in getting away from this beaty playing is to step away from the idea that we have to accent the downbeat of every measure. If we have a musical idea that spans four measures, and we accent the downbeat of each one, this just means we have taken one idea and unwittingly broken it up into four fragments.

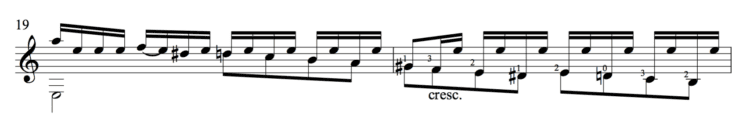

In the above example you can see an excerpt from Bach’s first cello suite (Prelude 1007) where the musical phrases do not start on the downbeat but rather start off the beat. If you were to accent the downbeat here, you would break the melodic contour.

The second most common culprit of beaty playing happens because of technical difficulty in the right or left hand. If there is a tricky shift, or chord shift, then we will often accent the right hand just because we are struggling with the left regardless of what the music needs.

One of the best ways to get around this is to have a clear idea of phrases, melodies, and musical gestures. Practicing melodies or bass lines in isolation will often remove a lot of the difficulty and help us to get used to hearing the idea as a whole. Then, when we re-inject the line back into the full texture we can better judge if we are being “beaty” or not. Similarly, singing will allow you to be musical without the technical challenges of the guitar getting in your way.

Above is an excerpt from the De Visee Prelude Repertoire Workbook. In the top line you will see the original music, which is quite dense with left hand chords. Underneath I have exploded the three voices that are in this piece. You can see that it will be a challenge to bring out these longer lines while navigating the chordal nature of the piece. This is one of the ongoing challenges of playing the classical guitar, and a prime candidate for “beaty” playing!

2. Let the music “breathe”

Singers need to breath in order to sing. As do flautists and saxophone players in order to play. Because of this they will often map out places in a score where they can musically fit it a small breath. Experienced musicians have excellent breath control so they can navigate long phrases with a single breath. When they finally do need to replenish their supply it can be such a discreet intake that the listener is more or less, unaware.

As guitarists we have little reason to be mindful of our breathing. Which is a shame, because it can help on several levels. The simple reason for this is that our fingers don’t need to breathe. They just keep on going…

That is all well and good for us, but for the listener the result is a performance that runs on without punctuation. Like a speaker that fails to pause, or a writer who cannot find the period (I’m looking at you Proust!).

Musical gestures and ideas get lost when playing becomes breathless, and things just get confusing to listen to. When things get confusing, people’s attention starts to wander.

To insert a breath into your playing I would first suggest to literally breathe. Sing the melodic line of what you are playing and find the logical points to add in a breath. Essentially, I want you to approach the score as a singer would and mark in places to breath.

Where do I breathe? I would suggest that phrases will give you the best place to start. We cover phrasing in-depth in the membership, but in short: a musical phrase is the smallest amount of material that could be considered an idea. There are short phrases, medium, and long phrases. There can also be phrases within phrases and ones that work together like a question and answer.

By adding in a slight pause, a breath, we allow these musical ideas to be identifiable, to be heard clearly. This means that when the ideas return in a repeat, or are developed throughout the piece the listener can identify and understand what is going on.

In summary, allowing a piece to breathe gives clarity and definition to musical ideas.

3. Suspensions

A suspension comprises of three parts:

- Preparation

- Suspension

- Resolution

The preparation is a standard triad. Let’s say C Major for a straight forward example:

C E G

From that C Major chord, we are going to move to a G Major Chord:

G B D

These two chords will form the outer two parts of our suspension, i.e. the preparation (C Major) and the resolution (G Major).

As we move between the two chords, instead of changing all of the notes we will have a chord in between where we will keep or “suspend” the C note from the C Major chord over the G Major chord. This C note will eventually resolve to the B in the G Major Chord.

Have a look at this piece by Sor to see suspensions in action (marked in blue):

The suspension figure is not always written out in full with a preparation chord, but the suspension/resolution figure is very common in classical guitar repertoire.

If you were to sing a suspension, the natural tendency would be to pull back on the last note, the resolving note. It is a relaxation of tension, and a harmonic resolution. So, playing the resolution more quietly than the suspension sounds good.

Guitarists will often accent the last note, or at best play it the same dynamic as the preceding note. This is simply because they are unaware of the suspension/resolution occurring, or they are not paying attention to how they treat the notes in the process.

The solution, once you have identified the suspension, is quite simple: To make this harmonic figure shine, resolve softly.

4. Moving parts vs. Static

Unless you are playing a single line melody, you are most likely dealing with melody plus chords and/or other voices (like a bass line for example). With all of these different musical parts vying for attention it can be challenging to make your musical ideas clear.

A general rule that can help bring clarity to the music is to bring out (play louder) the part that is moving and suppress (play softer) the part that is static.

For instance, a very common texture found in classical guitar music is to have repeated notes in the treble or the bass and then another voice that is moving against it. The technical term for this is oblique motion.

In this case we want to feature the moving part, the part that is changing pitches, and suppress the static part.

The example above is from Carcassi’s Etude 7, Op.60 (From the Level 3 Recital Book) and you can see the static part has a repeated “E” on the open first string throughout.

The example above is from Carcassi’s Etude 7, Op.60 (From the Level 3 Recital Book) and you can see the static part has a repeated “E” on the open first string throughout.

It sounds simple enough, but in reality the repeated notes are actually easier to bring out, and because the hand isn’t inherently musical it will just revert to whatever is easiest, unless you are paying attention.

More challenging still is when there is a static voice in the middle of the texture.

A classical example is the opening measures of Lágrima.

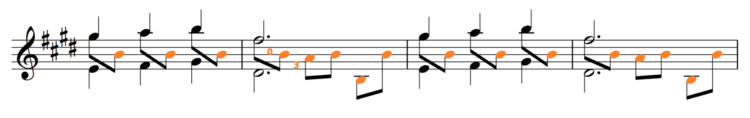

The middle voice (marked in orange) has several measures of static lines throughout the piece):

If the voice is played softly it provides a harmonic function. If it is played equally as loud as the other parts then it ends up sounding like it is part of the melody!

5. Never play a repeat the same way

This is what I would consider “low hanging fruit” in terms of injecting musicality into a performance. It is easy to do and all it really requires is an idea and a committed execution.

Repeated passages in music provide us with an opportunity to be creative as a performer. In all genres and levels of difficulty it is common to find sections that are repeated in their entirety. Perhaps it is a section marked with repeat signs, or perhaps it is a return of earlier material. In any case, you should take some time to explore what you can bring to the interpretation.

The most obvious choices are loud vs. soft or ponticello vs. tasto. They are “go-to” solutions for students when a teacher asks them for a form of variation and although they are obvious, that doesn’t mean that they aren’t as good as any of the other choices available. The real key to them is to commit to playing the variation all the way through the section. In the case of loud vs. soft I will often hear just a small difference between the two iterations when what I am really looking for is a immediate drop to a softer dynamic. Likewise with a right hand tone change, the right hand will often start returning to the normal position before the passage is finished.

But what else can we do?

Well, one option that offers a subtle change is to re-finger the passage for the left hand upon the repeat.

This obviously involves a bit more work in the learning process. (I would be lying if I wasn’t happy to see a large chunk of repeated material when learning a piece as a student! It always felt like I scored a free short cut.) However, it yields wonderfully musical results and encourages you to explore the fingerboard.

How about adding ornamentation?

Depending on the style and period of the piece, you could add in embellishments to the existing passage. A mordent, or trill, rolled chord or even augmenting some of the harmonies?

Adding these extra flourishes keeps the listeners ear engaged as they can’t presume to expect the same material to return the same way.

Articulation

Articulation is a good thing to be aware of at all times, but because of the sheer amount of possibility you can easily map out a different series of articulations for a repeat. Again this is just a situation where you need to spend some time exploring options and coming up with some new ideas.

All of the above

I would recommend starting out with just a single idea, so that you can execute it convincingly. However, once you have spent some time with the piece you can incorporate a mixture of variations that will be a treat to listen to. Furthermore, if you have invested the time to come up with various ideas you can keep yourself entertained by switching things up each time you play the piece.

Just the tip of the iceberg

These are just five guides to your interpretation, there are many more. If you have found this useful please comment below and let me know. If I get a positive response I can do another post.

Meanwhile, these topics and many more, are covered in the Technique and Musicianship courses from Level 1 through 4 in the CGC Membership. The lessons include homework, extended videos and examples.

This has been an interesting read. Parts I already try and adhere to, others I will have to revisit a few times to get fully acquainted, but overall a most useful series of concepts to improve one’s musicality. Great stuff!

This is really good to think about – so often we are soending most of out time on just hitting the right nites! I’m struggling with exercises involving suspensions currently, and had not heard an explanation of why the suspension was louder than the resolution – makes sense. I still find I dont notice them if there are ornaments in between the suspension and resolutuon though! Would really enjoy more articles like this, perhaps even with sound bite demonstrations

Hi Julie,

Yes, I intend to do a podcast on these topics so that I can offer sound examples but right now I am living in a very noisy house with musicians, babies, cats and dogs!

Great stuff Simon! This is timely with the repertoire I am working on now.

Glad you found it useful, Ken!

This is a positive response. You can now do another post.

Thanks, Simon. This is very helpful. I really enjoy these posts from you. Your topics address the very things I’m working on and thinking about. See you next month!

Thank you, Simon. This is well written, easy to understand, and removes a lot of mystery from the concept of “musicality”. Helps me begin to answer the question – now that I am playing the notes, what can I do to improve this piece?

Much food for thought! Thanks for your efforts to keep me musical

Hi Simon,

Thanks, I find your suggestions a helpful reminder. I wouldn’t mind a little clarification of phrasing on Bach’s first cello suite. By beginning each phrase on the offbeat and ending on the downbeat, doesn’t that actually reinforce the downbeat? I was taught to begin studies with 2-note-pair microphrases, followed by for instance larger one bar, two bar, four bar, and eight bar phrases. Each phrase begins on the offbeat and fininshes on the down beat of the final bar of that phrase. Within the larger phrases you should retain a clear sense of the micro phrases, without overshadowing the longer musical phrase. Would you use this approach, or do you take a different approach to phrasing?

Hi Simon,

Extremely useful practical tips….

I would welcome more of these…

Thank you.

Vic

Sunderland,

England

Hi Simon,

Definitely a very useful post. Thank you!

Linda

Great Simon!!!! Very good topics, and really usefull!

Thanks!

Thank you. this gave me new idea of thinking.

Thank you. Good food for thought. I would also like more if this.

I plan on thinking about refingering more after learning a piece to add some change and to help to get more use to playing at different areas of the fret board.

Really enjoyed the post. It helps me tremendously to see the music written out (I am a reader so I struggle sometimes with the visual lessons as there is a voice crying out somewhere to let me see the music!) I have been studying so far with teachers that are almost obsessive with timing, and I understand the purpose, but the idea of phrasing and ideas and breathing is new and just wonderful to put into practice.

Hi Simon, excellent post, very interesting and useful.

Definitely interpretation is what we need to transform a music sheet into a piece of music.

Thanks!

You know, the breathing idea to me just makes so much sense – a lightbulb moment I guess. Many thanks for that. You always come up with so much food for thought!!

Thanks, Simon, for presenting this. As a beginning classical guitar player but an experienced musician, I can confirm that info such as this is the reason I am a member of CGC. It is possible to find instruction on notes and technique, but very few teachers also include what it takes to play with expression and musicality. This marks CGC and your instruction as very high quality, a rare combination for any program, live or online! Keep up the good work!

Thank you Simon, this is a very interesting subject. When working on a piece, I try to listen to my “inner voice” to come up with an interpretation I like, but I often end up with nothing much satisfying. During my practices this week, I experimented with some of the notions you covered here and found that it is literally inspiring, especially the different possibilities to introduce variations in the repeats. This kind of topics feeds the inner voice, expands the limits of the “play ground”!

Excellent summary. I have been working on some simple scores so that musicality has a chance of being expressed.

The mistake of students solely playing or learning “aspirational pieces” does not allow for musical expression as note finding and technical issues become overwhelming .

This was an excellent article, Simon! All I can I add is make the effort to record yourself, so you can hear whether your intrepetation is effective or if it needs further tweaking.

Hi Simon,

I read this article now for the 2e time with attention

We devote hours months years of practicing and it cannot be said enough that the pleasure in the music starts with the most simple melodies played musically.

joannes

Hello Simon,

Useful and practical for all my repertoire. I never thought of re-fingering for adding interest. The right hand playing position is good to be reminded about as I know I’ve been guilty of moving it up the fingerboard when the intention was to keep in place for ponticello. Awareness is key. Also thanks for the detailed explanation of “beatiness”. I wasn’t quite clear on what that meant previously. Another fine podcast from you! Bonnie

Very informative with concrete steps to learn better musicality. Besides our singing the song I think recording our practices at various points, would help in learning whether or not we are achieving better musical performance. I will look forward to your recordings to demonstrate some of the sited passages.

Great article! Very well illustrated with examples and analogies, and very clearly written. Music is such a swamp! It really takes an incredible level of study and dedication to get half of it right, and we only live twice… But many thanks for being the guiding light in the valley of dark technicalities and unknown directions – it really helps!

Thank you very much, Simon, for another inspiring discourse on interpretation. This is a topic that has been both interesting and challenging for me; and it’s wonderful how your guide has fleshed out many of the things I have not verbalized to myself, and has shed light on some areas of confusion. I also particularly like what you said about musicality involving a musical syntax by which a shared feeling is communicated between strangers. Musical feelings are probably the hardest to define, and yet a key ingredient in music and interpretation. The ability to sense various nuances of emotion, in varying degrees, is probably the starting point in letting our fingers express these feelings in a way that our audience may experience the same.

Thanks for the article. I have a question that, somewhat, relates to the topic. What is the best external mic for a notepad for recording oneself playing the guitar. Or, more broadly speaking, what is the best way to record. Bob

Hi Robert,

Thanks for the comment and for your question. I’d recommend checking out Simon’s podcast on this topic here: https://www.classicalguitarcorner.com/cgc-018-recording-yourself/

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Thanks for another really helpful article, Simon. Before starting on classical I used the guitar mainly as accompaniment to songs which made my approach very “block chord” oriented. When I came to classical it took a long time to understand that the score was a aid to creating one’s own musical interpretation. I followed printed fingerings slavishly even when it was fairly obvious that some were typos! For me it’s now a joy to find a score without an editor’s fingerings added. Working out fingerings that suit both my hand and my interpretation really helps me understand the music (and the fretboard) a whole lot better. I really like your suggestion of using different fingerings sometimes on repeats.

Please print another one of these but with simpler, more melodic examples for us newbees. I understood, I think, the concepts, but when I tried to play the examples, I was distracted trying to make sense of the melody and fingering. Otherwise, you are opening a great many concepts around musicality for me..

Thanks for the awesome advice.

Thanks for these very useful tips. Another one that might be a good addition is staccato vs legato.

Very interesting ideas, thanks! I am a beginner. Should one master notes of a piece before dealing with the injecting musicality into the piece.

Very interesting, I was taught many years ago now that in private practice to sing out loud the melody to yourself. In Lagrima for example, is to imagine a ‘teardrop’ running from the eye down your cheek, and the shoulder movement of someone crying (the middle section).

Well explained article, very difficult to do.

Hi Simon, perhaps I’ve been playing suspensions incorrectly for too long but I’ve always felt that now that I’m finally playing the right cord tones I should give that a little more oomph. I’ve been trying it on the Sor study but it still seems a bit strange to me. Thanks though, I appreciate the advice. I like the idea of re-fingering – especially if it’s easy enough to pull off.