Dynamics on the Classical Guitar

In this article our Community Manager Dave Belcher talks about dynamics on the classical guitar. We’ll talk about dynamic range and contrast, especially exploring dynamic extremes, and the relationship between sound and silence.

***

In the silence of the night, interrupted by

the whispering aromatic breeze of

jasmines, the Guzlas accompany

the Serenatas and their fervent melodies,

which diffuse in the air notes as sweet as the sound

of the palms swaying in the sky above

– Isaac Albéniz, note on first page of “Córdoba” (Chants d’Espagne, Op. 232)

Dynamic Power

Dynamics in music can be a powerful thing. In fact, the word “dynamic” comes from the Greek word dynamis, which means “power.” Music has the power to move us, physically and emotionally, and well-sculpted dynamics can draw us in to what a performer wants to say, the story they’re trying to tell, the picture they are painting for us (to use non-musical analogies). However, a musical performance without dynamics can equally leave us feeling cold and unsatisfied. Music without dynamics is like coffee without caffeine or lightning without thunder. It is thus imperative that we learn to use dynamics appropriately and early on so that we can enrich our performances and give our music the power to move our audiences. In this article I’d like to talk further about dynamics and why it’s important to use dynamics effectively in classical guitar performance.

The quiet voice of the classical guitar

Because of the nature of plucked sound, the classical guitar has a rather limited dynamic range. The classical guitar, unlike its more audacious cousin, the electric guitar, is shy and has a quiet, tender voice. Nonetheless, the gentleness of the instrument is also one of its most attractive attributes and many are drawn to the classical guitar because of its warm, unassuming, almost romantic sound.

In order to preserve this quieter sound, Maestro Andres Segovia was steadfastly opposed to amplification of the guitar in his concert performances (Bream also eschewed amplification). Even when he performed concertos with orchestras, instead of amplifying the guitar Segovia would have the orchestra moved back so it would not drown out the guitar’s quiet voice. He required his audiences almost to have to strain, to lean in a bit to hear the soft whispering of the guitar in a concert’s most intimate moments. According to Segovia this quiet, charming aspect of the guitar was the “true sound of the instrument,”[2] a charm lost when others chose to amplify the sound.

Louder guitars

This did not stop him, however, from pressing luthiers, especially Hauser, to improve upon the volume of the guitar. And, largely due to Segovia’s efforts, today’s concert guitars are louder than ever. Amplification has also become much more acceptable in most venues and it would be a very rare event these days to hear a guitar concerto, for example, performed without amplification.

All of this means that, even though the natural sound of the guitar is still rather quiet, we have gained a greater dynamic range in the last half century. The challenge of the modern classical guitarist, then, is to utilize the improved dynamic range of the instrument while also preserving that quieter sound that gives the classical guitar its charm and appeal. It is thus up to us to explore a wider dynamic range in our playing.

Dynamic Extremes

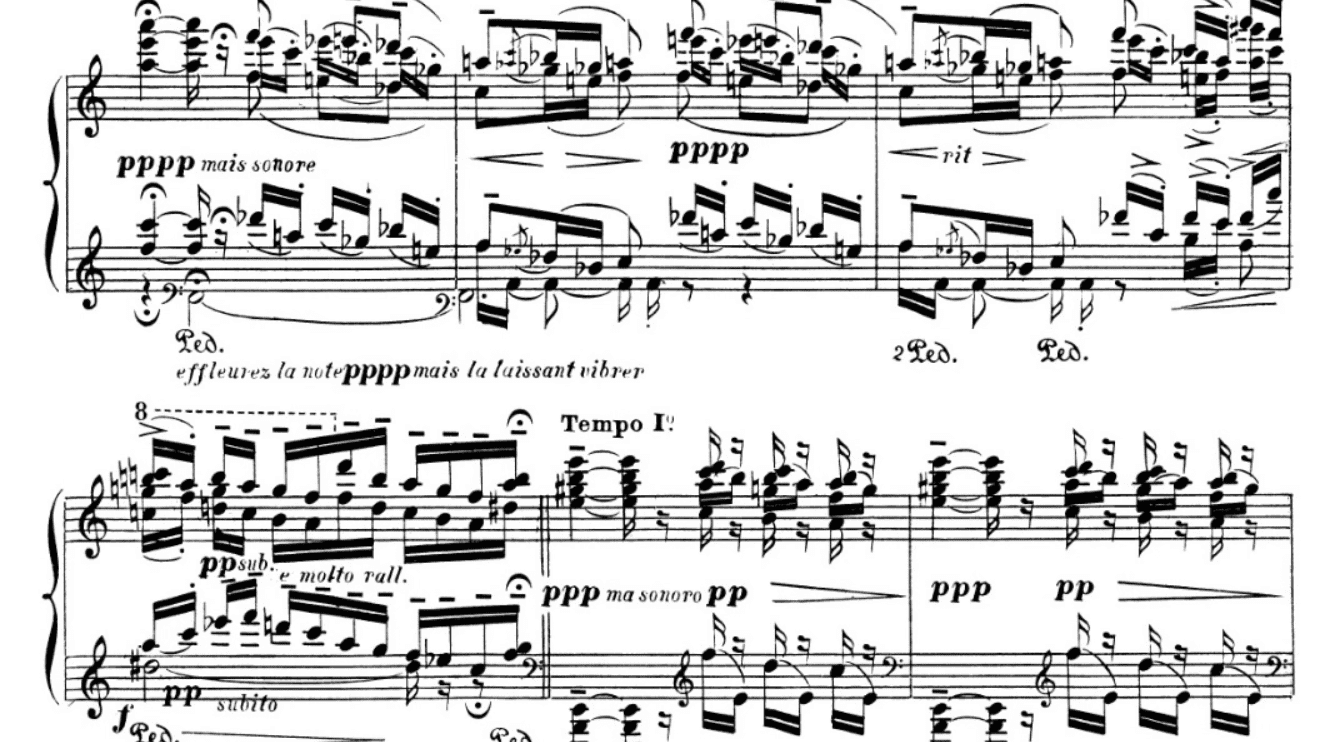

Dynamics is integral to music, so much so that not until the eighteenth century did composers start to use dynamic markings in their music. Prior to that dynamics was simply assumed to be a normal element in how a performer would interpret a piece of music. By the beginning of the twentieth century, however, composers began to use much more intricate markings for dynamics and extremes were widened to the point where some instructions were almost impractical. For instance in Isaac Albéniz‘s “Jerez” from Iberia—to take just one example—the composer includes the dynamic marking “pppp mais sonore” (quadruple pianissimo but sounding). This dynamic marking is accompanied by the performance instructions “effleurez la note pppp mais la laissant vibrer” (gently touching the note quadruple pianissimo but allowing it to ring).

Or take “Asturias,” a piece some of you may have heard of, where we have a swell from pianissimo to triple fortissimo, dying down at the end to a triple pianissimo.

Dynamics are relative

These kinds of extremes in the dynamic markings remind us of the common saying that dynamics are relative. How one performer chooses to execute a “pppp mais sonore” may be quite different from another. For this reason in some guitar editions of Albéniz‘s music, like Stanley Yates’s masterful set of transcriptions, you might find those triple and quadruple pianissimos simply changed to “normal” pianissimo. It is all relative, after all, how one wishes to interpret “pp” anyway. While that is certainly true we can also think about these extremes in more imaginative ways.

Distance?

Several years ago I saw Jorge Caballero perform some of his arrangements of Albéniz‘s Iberia and I asked him about those extreme, triple and even quadruple dynamic markings. He told me he thinks of those as less about volume and more about distance. Thinking of pianissimo more akin to the sound of distant church bells, or fortissimo more like, say, the horn of the car behind you not so politely asking you to go when the light turns green[2] can change the way we think about dynamics. Perhaps a quadruple pianissimo indicates something so distant that it comes to us almost as an otherworldly sound, a distant whispering from some other time or an unknown or forgotten place.

Infinitesimal pianissimo

To take another example, the Russian-French philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch (who was also a concert pianist) remarks in his book Music and the Ineffable that the pianissimos at the beginning and end of Debussy’s “Nuages,” the first of his Trois Nocturnes for orchestra (1899), “is an immaterial tremor, sliding silence and shuddering plumes: archangel wings brushing featherbed clouds would make no more noise than the violins’ shivering bows, and threefold pianissimo ‘ppp,’ fourfold, a thousand-fold ‘p‘ or a hundred-thousand-fold ‘p‘ would convey no more than the faintest idea of such an infinitesimal ‘piano.'” . . . “Archangelic hands would be needed,” to “extricate . . . every infratone and ultratone taken prisoner,” and they would “still be too heavy for this art of brushing lightly, for an immaterial contact even more imperceptible than the phantom touch of the asymptote.”[3]

Engaging in this sort of creative and imaginative process whereby we connect the music we are learning and performing with our world and experiences and even perhaps ideas, concepts, and images beyond our world and experiences can provide a deeper connection for our audience. Ultimately exploring both wider extremes of dynamics and new ways of thinking about and presenting those extremes in our performances will have greater emotional power for our audiences.

Dynamics and Silence

The Silence between the notes

As we continue to think more imaginatively about incorporating more dynamic extremes into our performances we should also keep in mind that silence is an integral part of a piece’s dynamic texture. Careful attention to the rests between notes not only can give rhythmic precision (as in the bass lines of Bach’s music for instance) or a certain cleanness to the sound but it can also accentuate the silence between the notes. Julian Bream famously remarked (echoing Debussy that “music is the silence between the notes”) that it is simply the nature of plucked sound that as soon as a note is plucked it is born and also immediately begins to die; and yet, he said, that is also the “poetry of plucked sound,” the space between the “birth” and “death” of a note.

Music as silence

Sound and silence have an intimate connection. Jankélévitch even talks about music as itself a form of silence, one that interrupts the noise of our everyday lives, the chatter of reason and metaphysics, and demands that it alone occupy audible “space” alongside these other noises that fill up our lives. When the conductor raises her baton to silence the squawks of the tuning orchestra at a concert, the voices of the muttering audience also become silent and music is then born from out of that silence.

Drawing attention to the silence of rests, breaths, breaks (the silence between the notes) in our performances can remind us (and so also our audiences) of the relationship of music’s sound and the silence of our conversation, the way in which we must quiet ourselves for music to sound. For it is only as we enter music’s silence that we can hear the notes as “sweet as the sound of the palms swaying in the sky above,” as Albéniz describes the Serenatas in his inscription to “Córdoba.”

Conclusion

Paying attention to dynamics in its varying aspects can help us shape the musical experience for our listeners. Music has the power to transport us into an entirely new sound world, one in which we discover all kinds of new and exciting and terrifying and wonderful and beautiful things. It is up to us to help take our listener there.

Notes

[1] Joseph McLellan, “Andres Segovia,” Washington Post, March 2, 1980 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1980/03/02/andres-segovia/df4b8cef-6e39-42c8-9dc2-ab1a5f48ac6e/?utm_term=.f2b04867b2bc). For more on how recordings have also changed the nature of the sound of the guitar, see Graham Wade’s article: http://classicalguitarmagazine.com/what-is-real-when-it-comes-to-guitar-sound/

[2] In a big city like New York, where I lived for a year, you hear distant car horns all the time even into the night, which after some acclimation can become almost like quiet lullabies lulling you to sleep, but they have an entirely different effect when a taxi lays on his horn while you’re in the middle of a crosswalk!

[3] Vladimir Jankélévitch, Music and the Ineffable (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 144-45.

Great article. Thank you.

I read this great quote in Mitch Albom’s “Magic Strings of Frankie Presto.”

“Music is not about playing louder, it’s about making the world quieter.”

Great quote, Rick! The philosopher I quoted, Jankelevitch, discusses exactly this same idea at great length (he calls it “the attenuation of reason” but I like Albom’s pithy saying a lot more).

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Thanks very much for that article Dave.

You’re welcome and thanks, Gerard!

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Thanks Dave! Great article. Playing the silence is definitely something I need to work on. Silence creates space and breath, but can also create great tension. Reminds me of 4’33” by John Cage.

Thanks, Scott! You’re absolutely right about the way silence can create tension. For some reason the first image that came to my mind was actually the interruption of John Williams’s beautiful score in Star Wars: The Last Jedi in a scene where all sound goes silent and we see brilliant flashes of light on screen before the sound returns (if you’ve seen the film you’ll know what I’m talking about). It’s a really gorgeous scene and adds so much tension and drama to the scene. Silence can do the same in our performances, especially when appropriate.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Thank you Dave! Very beautiful writing and very interesting content! I enjoyed a lot!

Thanks, Gino!

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Hi Dave,

a very good article.

i liked the remarks of Jorge Caballero when you asked him about those extreme, triple and even quadruple dynamics and he answered to think less about volume and more about distance.

thanks for sharing

regards,

Joannes

Thanks, Joannes! Glad you liked it. Yes, that conversation with Jorge was eye-opening. He does some other interesting things in his performances of Albeniz we talked about as well, like using campanella (a cross-string style of playing scalar passages from the baroque) and allowing the resonances of the strings to ring over one another, mimicking a sustain pedal. But in terms of dynamics I love the freedom to be imaginative with how we conceptualize extremes as well as gradual increases and decreases so his comments were particularly striking to me.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Fantastic insights about this aspect of playing classical guitar! Because the guitar is a relatively quiet instrument, I sometimes forget how important it is to prioritize dynamics and bring them out more creatively in my interpretations-thanks for sharing!

Thanks for the nice comment, Ben! Glad you found it helpful.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)