How well do you know your classical guitar notation?

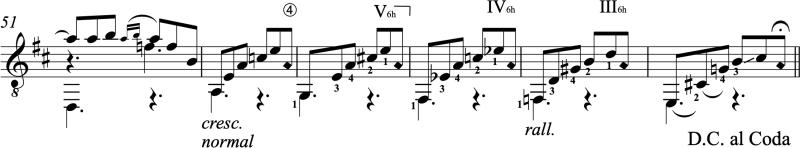

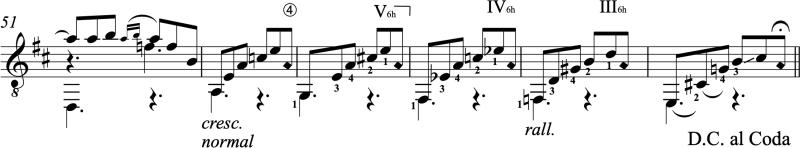

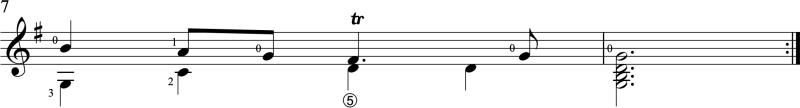

This example from “Julia Florida” by Agustin Barrios is a good example of just how many guitar notation symbols exist in our music. As teachers at CGC Academy, we see a lot of questions regarding the various marks that appear all over our music. So here is a guide to some of the most common notation symbols.

Finger numbers

Let’s start with the small numbers next to the notes. In the third measure (m.53) you see a 1 next to the G, 3 next to E, etc. These are left-hand finger numbers. They tell you which finger to play in the left hand. You can go here to read much more about guitar finger numbers and names. But to refresh your memory, here they are again:

- 1 – index

- 2- middle

- 3 – ring

- 4 – little/pinky

String numbers

Now look at the second measure (m.52) of the above score example. You see that circled 4 above the staff? What’s that? This is a string number. It tells you which string to play a note on. In this case you’re being asked to play a harmonic on the 4th string. (We’ll touch on harmonics below.) Go here if you need a refresher on your guitar string names and numbers.

Lines between notes

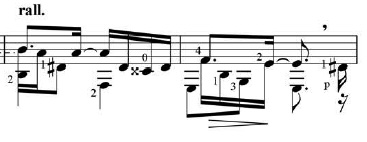

In the last measure of our Barrios example above, you see a line after the left-hand 3 between the B and the C. This can mean one of two different things.

- Glissando/portamento: In certain styles of music, a line like this will indicate that you should slide from one note to the next, keeping pressure on the string so we actually hear the first note, all notes in between, and the final note.

- Guide finger: In other cases the line simply tells you to use the same left-hand finger on both notes. This is known as a guide finger. Typically the way we will do this is to keep the finger on the string as we shift from one note to the next, but releasing pressure as we do so in order not to hear the notes between the first and second note.

But how do you know which to play? Usually a gliss./port. appears as a solid line between the two notes, while a guide finger will only be a dash next to the second note. However, this is not always the case! The most important way to distinguish these two is the style of the music you’re playing. Romantic music like Tárrega or Barrios will rely heavily on gliss.’s as part of the music’s style. But this kind of sound would be very unstylistic for Renaissance or Baroque music.

Barre

A barre allows us to play multiple notes across strings on one fret, usually by laying the first finger of the left hand flat across the strings. (Very rarely we might use a different finger, like the fourth.) Because these are so common, we have a symbol to tell us which fret to barre with the first finger and often how many strings we must barre. However, the symbols appear very differently across different scores. Here are some different ways the barre symbol appears in classical guitar scores:

- A common way is the use of capital Roman numerals to indicate which fret to play the barre on. For instance, in our above example “V” over the staff at the third measure would mean barre at the fifth fret.

- Sometimes the publisher/editor/composer will instead use an Arabic numeral to tell you which fret to barre. In most cases this will be preceded by either a “C” (for capodastro) or “B” (for barre). So, for instance, “C3” or “B3” would both mean barre at the third fret.

- Some publishers/editors/composers will also include how many strings you should barre. After all, not every barre is a six-string barre chord — thank goodness! Some will do so by using “1/2” to indicate a partial barre (only placing the barre on some, not all strings). Others will use “MC” to indicate a smaller barre. Still others will include a fraction out of 6, such as “4/6,” which tells you to barre 4 out of the 6 strings.

At Classical Guitar Corner, we have settled on using capital Roman numerals for the fret number, so III, and a small subscript number for the number of strings next to that. That looks like this:

At Classical Guitar Corner, we have settled on using capital Roman numerals for the fret number, so III, and a small subscript number for the number of strings next to that. That looks like this:- Most scores also include either a solid or dashed bracket to indicate how long you should hold the barre before releasing.

Hinge barre

You may also see other marks, like in our above Barrios example. The small “6” next to the Roman numeral “V” tells you how many strings to barre (here 6). The little “h” next to the “6” is asking you to do a hinge barre. This is a special kind of barre that can mean one of three different things:

- Play only the first string with the base of the first finger (usually in order to allow lower open strings to resonate before you lay the rest of the finger down for a full barre); or

- Play a bass note with the tip of the first finger while allowing open strings to resonate on the first or second strings and then close the hinge by laying the full barre down with the base of the first finger.

The hinge barre is a more advanced technique.

Harmonics

Harmonics are some of the most confusing symbols in all of classical guitar notation. Sometimes they appear as little circles above notes. Other times they appear as diamond-shaped noteheads. Still other times you will see “8va” or a capital Roman numeral above the note (not to be confused with the barre!). Add to all of this that we usually have different kinds of notation for natural and artificial harmonics and this gets to be a bit of a mess. In fact, virtuoso guitarist Gohar Vardanyan wrote a whole book on the topic of harmonics just to help students navigate some of this mess (highly recommended).

Natural Harmonics

Natural harmonics occur on open strings at particular frets, specifically frets 4, 5, 7, 9, and 12. There are other places you can play open natural harmonics (like fret 24 or even midway between frets 3 and 4) but the ones we just listed are the most common.

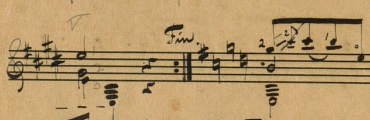

Fernando Sor is perhaps the first to notate harmonics in his music. He placed an Arabic numeral next to or below the note indicating which fret to play the harmonic and the note indicated which open string to play.

Sor’s Study 21 from Op.29 is a study played all in harmonics. For instance the first chord shows a fifth-fret harmonic on the open sixth string (tuned to D) and seventh-fret harmonics on the open third and second strings.

Franisco Tárrega used a similar notation, but wrote in “ar.” to indicate “armonico” next to the number.

Franisco Tárrega used a similar notation, but wrote in “ar.” to indicate “armonico” next to the number.

Other scores will use a small circle above the notehead to indicate that the note is a harmonic. Sometimes the note will be written at the sounding pitch and other times it will be written at the pitch of the open string.

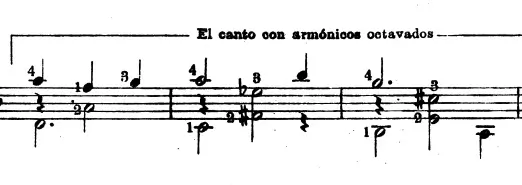

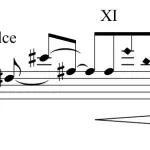

Much more common in modern notation, however, is to use diamond noteheads and either Arabic or Roman numerals for fret locations. Here’s an example from our CGC edition of Barrios’s “Julia Florida” we were looking at above. In the Coda section there are harmonics notated with diamond noteheads and Arabic numerals for fret locations above the notes.

Artificial Harmonics

Now what about that “Art.Arm. 8a” above the high D in the penultimate measure? This indicates artificial harmonics. These are played by fretting a note in the left hand and plucking with the right hand ring finger or thumb while holding the index finger over the fretwire 12 frets above the left-hand fretted note. In addition to “art. arm.” or “art. harm.” and “8a” or “8va,” you may see other signs, like “A.H.” or even just a Roman numeral, like “XIV.”

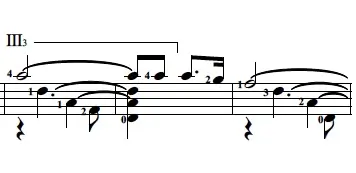

Miguel Llobet decided simply to write above the notes that the melody (canto) should be played with artificial harmonics.

Miguel Llobet decided simply to write above the notes that the melody (canto) should be played with artificial harmonics.

The more classical guitar scores you play the more kinds of symbols you will find for harmonics. Be patient and listen to recordings if you get lost.

***

Now let’s talk about some elements of navigation. There are several symbols that will tell you where to go in a score. Often we will repeat a section or jump back to the beginning or to some other point. These signs make navigating these jumps easier.

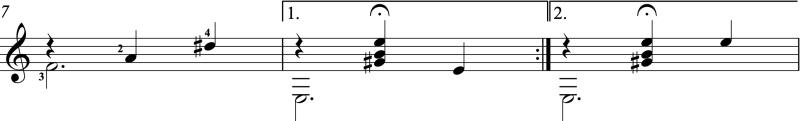

Repeats

A repeat sign is a bold double bar line with two dots next to it. This means you play up to the repeat sign and then go back to the beginning and continue playing past the repeat sign. However, sometimes you will also see a forward-facing repeat sign. This is known as an “open repeat” sign (the ending repeat is a “closed repeat”). In this case, you play up to the repeat sign and then go back to the “open repeat” sign and continue playing past the repeat sign.

1st and 2nd endings

Another common element of navigation in music notation is 1st and 2nd endings. These are repeated sections with a different ending the second time through from the first time. To play them, play all the way up to the repeat sign underneath the “1” with bracket, then return to the beginning and play up to the first ending mark and skip to the “2” with bracket and continue forward. Here’s an example:

D.C., Da Capo al Fine

Sometimes you will need to return to the beginning of a piece but without repeat signs. In these cases you may see “Da Capo” (or “D.C.”), which means “to the head” or to the beginning. This means you return to the beginning and play again up to the end. Sometimes the composer will ask you to return to the beginning but place the ending earlier in the piece. In this case, you will see “Fine” (end) marked in the middle of the score and at the end of the score “D.C. al Fine.” All this is asking you to do is to play the whole piece, return to the beginning, and end at the “Fine” mark.

Notice how in the above example the “Fine” comes at measure 8. So here you would play all the way up through measure 24, return to the beginning, and play up to measure 8, which is the end.

D.S., Da Segno al Fine

Another common term you will see is “D.S.” or “Da Segno.” This indicates that you should return to the segno or sign, which like the Fine will be placed earlier in the piece. D.S. just means to return to the sign and continue to play to the end (unless there are other navigations afterwards). The sign looks like a squiggly S with a line through it and dots on either side, like this:

Another common term you will see is “D.S.” or “Da Segno.” This indicates that you should return to the segno or sign, which like the Fine will be placed earlier in the piece. D.S. just means to return to the sign and continue to play to the end (unless there are other navigations afterwards). The sign looks like a squiggly S with a line through it and dots on either side, like this:

If you see “D.S. al Fine” that means to play up you return to the sign and then play up to “Fine.”

D.S., D.C. al Coda

Finally, another important navigation mark is the coda. Coda means “tail” and is like a tagged on ending. Our first example, Barrios’s “Julia Florida,” uses a Coda. The Coda has a special sign (an oval with a vertical line through it) and can will usually be combined with several different instructions.

- D.S. al Coda means to return to the sign (our squiggly S above) and then to play up to the Coda sign (the oval with the line through it) and jump to the end which will have that same Coda sign above it with “Coda” written next to the symbol.

- D.C. al Coda means to return to the beginning and when you get to the Coda sign (oval with line through it), jump to the end with the Coda sign and “Coda” written next to the symbol.

Here’s what all of that looks like:

Dynamics

Dynamic marks and symbols in music notation tell us how loudly we should play. Here are the common dynamic symbols:

- p: piano — soft

- f: forte — loud

- mp: mezzo piano — moderately soft

- mf: mezzo forte — moderately loud

- pp: pianissimo — very soft

- ff: fortissimo — very loud

- sfz: sforzando / sforzato — with effort or suddenly loud

- pf: poco forte — play stronger with fullness but with the same sensitivity as piano (this pops up in Carulli’s music)

- cresc.: crescendo — gradually get louder (often accompanied by dashed line indicating loudest point)

- decresc.: decrescendo — gradually get softer (often accompanied by dashed line indicating softest point)

- dim.: diminuendo — gradually get softer (often with the sense of dying away)

- morendo: dying — gradually fading to nothing

- à niente: to nothing —gradually fading to nothing

Hairpin dynamics

Hairpins are symbols showing swells and decays in dynamics. Sometimes they are accompanied by other signs like above, and sometimes not.

Articulation

Like in speech, we can affect the meaning and feel of music by how we articulate certain notes. We can do this through accents, tying notes together, and shortening notes, among other things. Here are the most important articulation symbols:

Accents

Accents look like a sideways wedge or incomplete triangle above a note. Typically accents are interpreted to mean play the note louder. However, it only really means we should emphasize that note in some way. Sometimes they tell you to bring out a melody while at other times they work with the musical ideas present. For instance, here in Tárrega’s Prelude 1 in D minor, accents are placed on the first notes of pairs of slurs. Musically a slur between two notes has a natural strong-weak relationship.

Staccato

The Italian word staccato means “detached,” and so you should play these notes shorter than their written duration. Staccato appears as a small dot below or above the notehead:

Tenuto

Tenuto means “held” and usually means you should hold on to a note for slightly longer than its written duration. This is the meaning in the Coda from Barrios’s “Julia Florida,” where “ten.” asks you to hold the last A of measure 58 slightly longer before moving on to the last few measures.

Another way tenuto can appear in notation, however, is as a solid line above a note or notes. And while sometimes this has the same meaning as above, it can also mean to play the note for its full duration. In other contexts it can be used to tell you what the melody notes are. For instance, in Sergio Assad’s Aquarelle, mvt.3, tenuto marks identify melody notes and also tell the guitarist to play these notes for their full duration (in contrast to staccato notes in surrounding context).

Another way tenuto can appear in notation, however, is as a solid line above a note or notes. And while sometimes this has the same meaning as above, it can also mean to play the note for its full duration. In other contexts it can be used to tell you what the melody notes are. For instance, in Sergio Assad’s Aquarelle, mvt.3, tenuto marks identify melody notes and also tell the guitarist to play these notes for their full duration (in contrast to staccato notes in surrounding context).

Roland Dyens uses a solid line above a chord to indicate it should be played as a block chord, not arpeggiated.

Slurs, Ties, Phrases

One very confusing symbol in music notation is the curved line, because it can mean one of four different things: slurs, ties, phrases, or to let notes ring longer than their written duration.

Slur

A slur connects two or more notes in a legato, or connected, way.

- Dashed slurs: Occasionally you will see a slur mark with a dashed curved line. These are called editorial slurs and usually indicate that they are optional. Often a slur can make a technically difficult passage easier. However, if a slur was not present in the original edition (say, of a transcription), then a dashed slur gives you an option to make that passage technically easier.

Tie

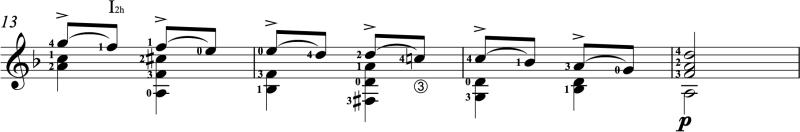

A tie connects two notes of the same pitch, sometimes across barlines. The tie indicates that you should continue holding the note for the combined durations of the two notes. For instance, in Aguado’s “Menuet” below, the A in the bass at measure 13 should be held for 5 full beats (3+2).

Phrase

A phrase mark is a longer curved line that identifies a full phrase (or complete musical idea). Sometimes, however, these can be shorter curved lines and so it’s important to distinguish between these shorter phrase marks and longer slur marks. In the example below from J.S. Bach’s “Prelude BWV1007,” the longer curved lines are phrase marks, while the short curved lines starting in m.24 are slur marks:

Sustain / laissez vibrer

Another way curved lines appear in music notation is extending from one note but not connecting to another, like this:

Another way curved lines appear in music notation is extending from one note but not connecting to another, like this:

In other places, the composer (in this case Stephen Goss) may write “l.v.” or “laissez vibrer” to indicate the same thing: let the notes ring or vibrate.

Time

Fermata

A fermata is a bird’s-eye symbol above a note telling you to hold that note or notes for an unspecified length of time. How long you hold the fermata is up to you and the context of the music. For a shorter piece of music, you might pause for a shorter duration in the music. In the example from Tárrega’s “Estudio in E minor” below, the fermata appears above the last chord in measure 8.

Breath mark / comma / caesura

Sometimes a composer will include a comma above the staff, which asks you to pause briefly, like taking a breath, before moving on. Again, how long you pause is up to you, but it should be shorter than the pause at a fermata.

Rests

A peculiar feature of classical guitar notation in particular is that sometimes a rest appears only to fill out the durations for one voice in a measure. That is, the rest does not mean you need to play the rest. Knowing when to allow notes to ring or to stop them (playing the rests) will take some knowledge of the style and using your ear.

Arpeggiated chord symbol

Arpeggiated or rolled chords sound really nice on the guitar. And while this is really a special effect we should be careful not to overuse, sometimes a composer will ask you to roll a particular chord. The symbol for that in guitar notation looks like a squiggly line.

Rolled chord written out in notation

In other instances, a rolled chord will be written out in notation with its precise rhythmic execution. Usually this kind of rolled chord will appear as 32nd or 64th notes.

Color changes

In addition to volume, articulation, and indications for how long to play a note, other signs tell us what kind of colors to use.

- pont. or ponticello: Play closer to the bridge for a brighter sound

- tasto or sul tasto or tastiera: Play closer to the soundhole or even over the neck for a warmer sound

- dolce: Often synonymous with tasto, this means to play “sweetly”

- metal. or metalico: Often synonymous with pont., this means to play with a “metallic” sound

Ornaments

There are many ornaments or embellishments in classical guitar music, some written out in notation, other times with symbols.

Grace notes

A grace note appears as a smaller note or set of notes next to a larger “principal” note. Grace notes sometimes have slashes through the stems and other times do not. A great example is Study No.8, Op.6 by Fernando Sor:

The difference between the grace notes with and without slashes through the stems affects how you play each of these ornaments.

- Appoggiatura: The notes without slashes through the stems are appoggiaturas and mean you play them on the beat with an emphasis on the grace note and relaxing on the resolution to the principal note. Thus, these function like suspensions and resolutions. Typically appoggiaturas take half the value of the note they are attached to. So in the above example, we will play the G appoggiaturas in measures 14 and 16 for one quarter note (half of the half notes they are attached to).

- Acciaccatura: The notes with slashes through the stems are acciaccaturas and mean you play them quickly and lightly with the emphasis on the principal note. Whether the grace should be played on or before the beat will depend on style and context. Here (measures 38 and 39) they are played on the beat.

Mordent

A mordent can mean a few different things depending on the style and context. In Baroque music, the mordent often appears as a chevron symbol with a vertical line through the middle. The mordent should be performed by playing the written note and quickly moving one diatonic step below the note and back. So in the example below, the mordent symbol over the B means to play B-A-B rapidly.

Trill

The trill symbol sometimes looks very similar to the mordent symbol. It will often appear as a chevron, but without a line through the middle, like this:

However, in other instances the composer will write “tr” above the staff to indicate a trill. In J.S. Bach’s music, tr is by far the more common symbol. A trill means you play the note and alternate with its upper diatonic neighbor. So in the case of the Allemande above, you would play the B trill in measure 13 in either one of two ways: 1. C-B-C-B; 2. B-C-B. Whether to start with the principal note (B) or the upper auxiliary (C) depends on context, style, and interpretation. Below is the tr symbol in Bach’s “Bourree.”

Metric Modulation or Tempo Equivalents

There are many situations in music where the time signature might change. This usually will mean the rhythmic feel of the piece (its “meter”) will also change. In some of these scenarios, a composer will include a metro modulation, also known as a tempo equivalent to tell you how to interpret the change. For instance, John Dowland’s “Fantasia P1a” is in cut time (a feel of two beats per measure). However, at the end of the piece it changes to a triple meter in a feel of four beats per measure. The metric modulation above the staff, quarter=dotted quarter, tells the performer that the duration of a quarter note in the previous section is now equal to the duration of a dotted quarter note. That means this section will feel one and a half times faster.

Key Changes

In other situations we might move to a new key and as a result the key signature might also change. The new key signature will sometimes include natural signs in the key signature to remind you that previous sharps or flats are no longer sharp or flat in the new key signature. This happens in the middle section of “Lágrima” by Tárrega:

In other situations we might move to a new key and as a result the key signature might also change. The new key signature will sometimes include natural signs in the key signature to remind you that previous sharps or flats are no longer sharp or flat in the new key signature. This happens in the middle section of “Lágrima” by Tárrega:

Pizzicato

A fairly common extended technique on the guitar is “pizzicato” (also known as etouffé) where we play notes muted. The most efficient way to perform pizzicato is to lay the flesh of the right side of the palm of the hand just to the left of the bridge so that you still hear the pitch of the notes when you pluck with the thumb and/or fingers. This appears as “pizz.” next to notes that should be played this way.

Bartók pizz.: Less common is what is known as Bartók pizzicato (or “Bartók pizz.”) named for Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. To play Bartók pizz., grab the string with the thumb and index finger and pull it straight up away from the top of the guitar and release to create a forceful slap against the frets. The symbol for Bartók pizz. looks like a power button.

Bartók pizz.: Less common is what is known as Bartók pizzicato (or “Bartók pizz.”) named for Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. To play Bartók pizz., grab the string with the thumb and index finger and pull it straight up away from the top of the guitar and release to create a forceful slap against the frets. The symbol for Bartók pizz. looks like a power button.

Rasgueado strums

While strumming is not as common in classical guitar music as it is in other guitar styles, rasgueado strumming is indeed quite common in Spanish guitar music. If you play music of Rodrigo, Sainz de la Maza, or flamenco, you will see markings for rasgueado strums. While there are numerous ways composers notate a rasgueado (like harmonics), the most typical is an arrow pointing in the direction of the strum. Sometimes the line of the arrow will be a squiggly line, like with rolled chords, and other times it will be a straight line.

m.d. and m.g.

Less common abbreviations you will see (often in more advanced pieces) are “m.d.” and “m.g.” These stand for “maine droite” (right hand) and “maine gauche” (left hand) in French. They signify that you should play that note with just that hand. The abbreviation “m.d.” is typically used for right-hand-only natural harmonics. For instance, if you are holding a note or notes in a lower position but need to play a 12th-fret harmonic, you can play that harmonic with the right hand alone, like an artificial harmonic. By contrast, “m.g.” is much less common and can range from playing a whole section with only the left hand (all hammer-on and pull-off slurs) or just to play one note with the left hand alone.

- m.d. – right hand only

- m.g. – left hand only

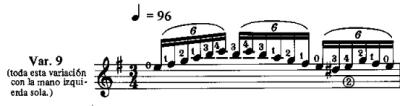

In Llobet’s Variaciones sobre un Tema de Sor he does not use “m.g.” but writes instructions for how to play the variation.

In Llobet’s Variaciones sobre un Tema de Sor he does not use “m.g.” but writes instructions for how to play the variation.

Percussion

There are several different kinds of percussion notation symbols you might encounter. We’ll list a few here, but if you’re really interested in learning about nearly all of the possibilities out there, you should consult good friend of CGC Manny Auciello’s master’s thesis on the topic. (There is a whole appendix starting on p.55 with a list of different percussive effects in repertoire along with images of the symbols used.)

- Tambora

- Golpe

- String hit

- other

8va

The abbreviation 8va means “ottava” or octave. It means to play the indicated passage either up or down one octave, depending on the context. (Typically if this is written above the staff you’d play the passage up an octave; below the staff and play down one octave.) We saw above how this can be used for artificial harmonics. In other cases it tells the guitarist to play a single note down one octave if they are using a guitar with more than six strings.

The abbreviation 8va means “ottava” or octave. It means to play the indicated passage either up or down one octave, depending on the context. (Typically if this is written above the staff you’d play the passage up an octave; below the staff and play down one octave.) We saw above how this can be used for artificial harmonics. In other cases it tells the guitarist to play a single note down one octave if they are using a guitar with more than six strings.

For instance, J.K. Mertz played on a 10-string guitar and would write “8va” on notes that originally sounded one octave lower on his guitar. He would also sometimes write “loco” next to 8va to cancel the octave. (No, it does not mean go crazy at the octave!) This happens in his “Fantasie Hongroise.” In these contexts, even though Mertz played that note an octave below, a six-string guitarist can play the note as written.

Tremolo slash

One or multiple slashes through the stems of notes usually means to repeat that note or notes (usually the number of slashes dictates the subdivision, or how many times to repeat). For instance, in Villa-Lobos’s “Etude 4” there are double slashes through the stems of quarter notes, which means to play four sixteenth notes for each quarter. The single slash through the eighth note stems mean to play two sixteenths for each eighth.

One or multiple slashes through the stems of notes usually means to repeat that note or notes (usually the number of slashes dictates the subdivision, or how many times to repeat). For instance, in Villa-Lobos’s “Etude 4” there are double slashes through the stems of quarter notes, which means to play four sixteenth notes for each quarter. The single slash through the eighth note stems mean to play two sixteenths for each eighth.

Dyens’s bass stopping

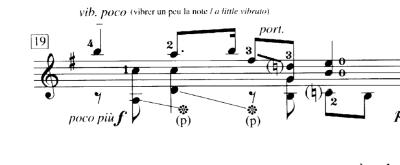

There is likely no other composer who includes more unique symbols and markings in his notation than Roland Dyens. His scores are meticulous and filled with all kinds of notes. One of the most common symbols Dyens uses is the asterisk, which he uses to indicate you should stop a previously ringing bass note. That looks like this:

There is likely no other composer who includes more unique symbols and markings in his notation than Roland Dyens. His scores are meticulous and filled with all kinds of notes. One of the most common symbols Dyens uses is the asterisk, which he uses to indicate you should stop a previously ringing bass note. That looks like this:

***

While this is a fairly comprehensive guide, believe it or not this is not an exhaustive list of all guitar notation symbols! You may see other strange things in your scores. Either way, we hope this has been helpful and gets you back to playing! Post any questions you have in the comments.

If you’re still a beginner, learn how to read guitar sheet music first.

m.d. = main droite (not maine droite) – ;simile for m.g.)