Learning how to read guitar sheet music can be similar to learning a language. It will take time, experience, and repetition to gain a sense of ease and fluency. It is not unusual to feel a sense of overwhelm during this process especially as you will encounter many new concepts and terms. Allow yourself time to let things sink in and trust that with practical experience abstract ideas will become clear.

Guitar Sheet Music Overview

Score, Partitura, Sheet Music, Chart, Piece, Song, Standard

A piece of sheet music in the classical music tradition is called a score. In addition, you will find it called partitura (Spanish), or perhaps a manuscript. Other common terms for guitar sheet music such as song, chart, or standard are used in other genres of music like folk, pop, or jazz.

Title, subtitle, composer and edition

At the top of your sheet music you will find important information. These include the title, subtitle, composer, editor, arranger, and publication details. If you find a set of dates next to the composer’s name it will be indicating when they were born. This can be useful to understand when the composer lived and therefore what period and style of music they composed in.

The Musical Staff and the Musical Alphabet

The Staff

A music staff consists of horizontal lines and spaces that denote different pitches. For the classical guitar we have five horizontal lines and four spaces within those lines. Note heads appear either on a line or in a space. As notes move up the staff their pitch will be higher. As they move down, their pitch will be lower.

Because the range of the guitar is extends beyond the five lines of the musical staff, extra lines appear to accommodate higher and lower notes. These are called ledger lines and follow the same use of lines and spaces.

The Musical Alphabet

The musical alphabet goes from A to G. ABCDEFG. There is no “H” note in the musical language. Rather, when the cycle of notes from A to G is completed it simply starts again.

ABCDEFGABCD

Or, if the notes are descending: AGFEDCBAGFED

The staff helps us navigate the musical alphabet in a very logical way. Each line and space represents a single pitch from the musical alphabet. If you move up to the next line or space you will have moved up one note in the musical alphabet. From A to B for example. If you move down one line or space you will have moved down one pitch in the musical alphabet. From A to G for example.

The Treble Clef and the Octave

The simple logic of the music staff is easy to use. However, it is missing one important thing, a starting point! Different clefs appear on the score to provide different starting points for the musical alphabet. For the classical guitar we use the treble clef.

This clef, which majority of instruments use, is also known as the G clef. Its name comes from the symbol that centers around the second line from the bottom. The note there is G. And this provides a starting point for all other notes around it.

One peculiarity to the classical guitar is that the notes in classical guitar music actually sound one octave lower than they normally would on the treble clef. This does not affect your reading of the notation. But if you play the same note on the staff as a violinist they will sound an octave apart. The technically correct clef for the classical guitar has a small 8 written below the clef. This indicates that the pitch is an octave lower. Often, however, is left out.

Music Systems in Guitar Sheet Music

A single staff of guitar sheet music can only hold so much information. As it flows down the page from left to right and top to bottom we need another term to communicate what line of music we are on. This term is system. Just as you might refer to a line in a book of text we refer to systems in a musical score.

A system can have a single staff as it often does in solo classical guitar music, but it can also refer to groups of instruments using multiple staffs in ensemble scores.

Note Heads and Stems

The horizontal lines and spaces of a staff communicate pitch, but they don’t tell us anything about rhythm. Rhythm is communicated with different note values that can be differentiated by the note heads, stems, and ties.

Note heads can be either hollow or filled in. They will be placed either on a line or in a space on the staff to communicate pitch. The duration of a note will be communicated by the note head being hollow or filled in, with or without a dot, and also the type of stem that is attached or absent from from the note head.

The direction of stems will change depending on the location of the note head. Notes above the middle line will often have downward stems and those below will have upward stems. This is largely for practical space-saving reasons on the score. As musical textures get more complex you will find directions might depend on what notes relate to each other for melody, bass, and accompaniment.

Time Signatures and Measure Lines

Having note durations on a score are not that useful until they are organized and grouped together. That’s where time signatures and measures come into play.

Time signatures appear at the beginning of pieces. They can also change at different points in the music as it progresses. They help us group rhythms together. Moreover, they can communicate a musical feel or dance such as a waltz, march, jig, or mazurka. A time signature usually has two number stacked on top of each other. The top number tells us how many beats are in each measure. The bottom number tells us what kind of beat it is.

A measure (or bar as it is sometimes called) helps us group rhythms together into understandable chunks. The time signature defines the rhythmic capacity of a measure and once it is full we use a measure line to denote the start of another measure.

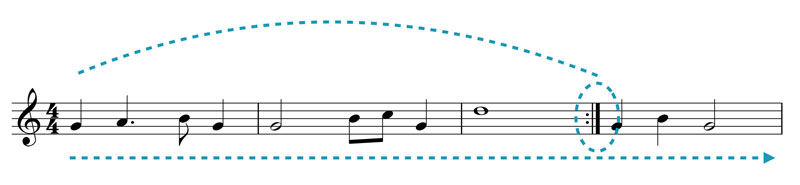

Repeats

Repetition is common in music and instead of re-writing a passage that is repeated we can simply use repeat signs in place of the normal measure lines. Once we arrive at a repeat sign we return to the beginning of the score and repeat the music once unless there is a forward facing repeat sign in which case we only return to that point in the score and move onwards from there.

Guitar Tablature (TAB) vs. Standard Notation

Learning how to read guitar sheet music can feel overwhelming. Tablature or TAB offers a simple and quick way to communicate where a note or group of notes is to be played on the guitar.

At its core, TAB tells you what string to play and which fret to hold down. You can get quite a long way with these two simple instructions. And that is why TAB is such a popular way to learn guitar music.

TAB has six horizontal lines, each one represents a string on the guitar. The top line represents string #1 E and the bottom is #6 low E. When there is a number on that line, it means to play the note at the corresponding fret number. For example, if there is a 1 on the second line from the top, it means play the first fret on the second string. If there are numbers stacked on top of each other over different strings it means that you have to hold down all those notes and play a chord.

Right-Hand Names on Guitar

The letters p i m and a are used on the score to communicate right-hand fingerings.

The letters p i m and a are used on the score to communicate right-hand fingerings. - The letter p refers to the thumb and refers to the Spanish word for thumb pulgar.

- The letter i refers to the index finger and comes from the Spanish word for index finger indice.

- The letter m refers to the index finger and comes from the Spanish word for the middle finger medio.

- The letter a refers to the index finger and comes from the Spanish word for the ring finger anular.

There is a letter for the little finger, although you will not find it very often in classical guitar music because it is seldom used. That letter is c for chico, which translates to little finger.

These letters can be found individually or stacked together. They are placed as close as possible to the note they are referring to and can be found above or below the staff depending on what offers the clearest instruction.

In the early stages of learning you will find a lot of right-hand fingerings to help you develop good habits and support reading fluency. As you progress past the beginning stages, however, you will notice that there is less right-hand fingering on the score. This happens for a number of reasons.

- The fingering is deemed obvious by the editor and is unnecessary to be written out on the score.

- There are multiple approaches to the fingering choice and the editor doesn’t want to dictate each choice.

- To keep a score uncluttered by removing text that isn’t absolutely necessary.

- In an educational setting you also might find an occasion where the problem solving process provides a learning opportunity and therefore fingerings are omitted intentionally to get you engaged in the process.

Left-Hand Numbers on Guitar

On the score you will find the numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 used to communicate left hand fingerings.

On the score you will find the numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 used to communicate left hand fingerings.

- 1 refers to the index finger.

- 2 refers to the middle finger.

- 3 refers to the ring finger.

- 4 refers to the little finger.

Just as with right-hand fingering you will find the numbers placed as close as possible to the notehead so as to be clear with fingering instruction. These numbers can be in isolation for an individual note or stacked next to a chord. Sometimes their placement can be moved around by other objects on the score, like sharps or flats, and this makes their placement a little less consistent. The numbers can be found to the left or right of a note head and even above or below.

Similar to right hand fingering you will find an abundance of fingering in beginner materials and less in advancing repertoire. Overall, however, you will encounter more left-hand fingering than right because the solutions are less obvious. As you progress in your studies you will find that left-hand fingering becomes integral to learning and interpreting repertoire. Advanced players will often seek out fingering solutions to pieces or passages from master players to discover how they made technical and musical choices. If you love puzzles, you might find that you enjoy the challenge of left hand fingering!

Guitar String Numbers

Guitar string numbers found in circles are referring to a specific string on the guitar. The guitar has six strings and therefore you will find the numbers 1 through 6 in circles on the score. Because there are several places to play a single pitch on the guitar (sometimes as many as four practical locations to choose from) it can be helpful for the editor or composer to specify what string is to be used. Using the string number in conjunction with the left-hand fingering offers a good deal of information as to where and how to place your fingers.

Guitar Positions

A guitar position is determined by where your first finger falls on the fingerboard. In guitar sheet music you will sometimes find indications telling you what position to play. This helps you understand where on the guitar fingerboard to look for the right notes.

First position, for example, is when you use your first finger for notes on the first fret. In this position you will generally find that your second finger plays the second fret, the third finger plays the third fret, and the fourth finger plays the fourth fret. This is called the “one finger per fret” rule.

If we are translate this up one fret, then the first finger plays the second fret, the second finger plays the fourth fret, and so on. This would be second position. If you translate all of this up the fingerboard where your first finger is on the fifth fret you would be in fifth position. It is that simple.

While using one finger per fret can be quite consistent with simple melodies this “rule” is quickly broken as soon as we start playing more than one note at a time. It can be a bit of a sticking point for beginners when fingering moves away from the one finger per fret rule so it is good to acknowledge early on that positions simply communicate an area on the fingerboard in which to play rather than which fingers to use. Positions are also rarely static as the left hand moves constantly up and down the fingerboard. Once again, more of a communication tool than a playing tool.

Further Resources on How to Read Guitar Sheet Music

The Cornerstone Method for Classical Guitar : A step-by-step method that will teach you how to read sheet music on the classical guitar.

Guitar Notation Symbols: A comprehensive guide to symbols that appear in guitar sheet music.

CGC Academy : A complete curriculum for classical guitar study that will not only teach you how to read sheet music for guitar but also guide you through technique, repertoire, practice skills, and theory.

Leave A Comment