A phrase is a line of music that presents a complete idea.

It is quite an ambiguous term, and there are many variations possible, however phrasing is crucial to making music as it tells us how notes relate to one another, rather than being isolated dots on a page.

The concept itself is very familiar to us as we speak in phrases on a daily basis. We understand that to speak a phrase/sentence/idea convincingly and clearly we have to have a concept of it before we begin, otherwise it might come out a bit haphazard.

When I was in high school, the English class would read through Shakespeare plays and various students would get assigned roles as the others followed along. I was really into theatre at the time, so when I was given a role to speak I would be constantly jumping ahead to read my part and prepare the phrasing before it was my turn to speak. If I didn’t get that preparation time then I would often stumble on words, give them the wrong inflection, and get the pacing all wrong.

The same thing can happen if you don’t think about phrasing in music. If it is just a series of little connected moments then it will be hard for the listener to know how it all makes sense together. Similar to Shakespeare, notated language might not be entirely comfortable for you right now, so it is important to take time specifically to look at the phrasing.

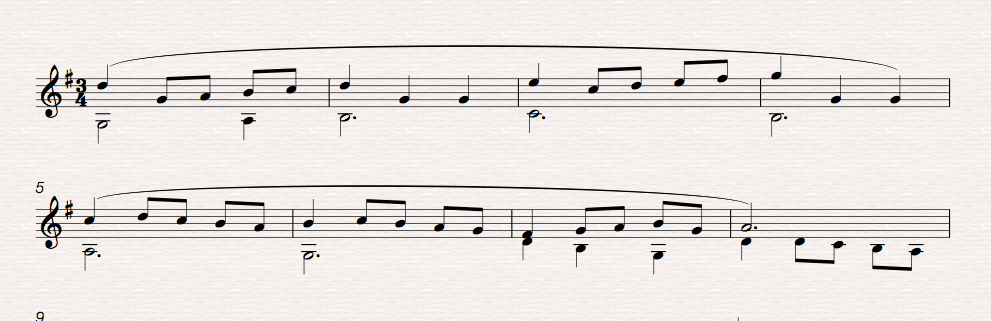

Composers and editors are often doing their best to help delineate phrases and they mark out the connections with big long arches like this:

If you ever see one of these, then give the editor a big pat on the back because they have done you a big favor. If the phrasing is not marked in, it is a wonderful idea for you to sit down away from the guitar and mark up your score. Phases can span large sections and run on quite a while, or they can sometimes be quite brief. They can also elide with one another (one finishes where the other begins) Luckily for us, phrases are usually pretty clear, at least once you get used to identifying them. In the example above we have a pair of phrases that compliment one another. You could call this pairing “call and answer”.

In classical music you will often have two phrases that act as a somewhat ‘Call and Answer” relationship. These phrase pairs are often defined by the first ending in an imperfect phrase (the dominant chord or V chord, for example the chord of G in the Key of C) and the second, ‘answering’ phrase will end in a perfect cadence (V going to I – dominant to tonic – eg. G to C) If you hear enough of these phrases you will start to recognize them as a listener and you won’t even have to see the score!

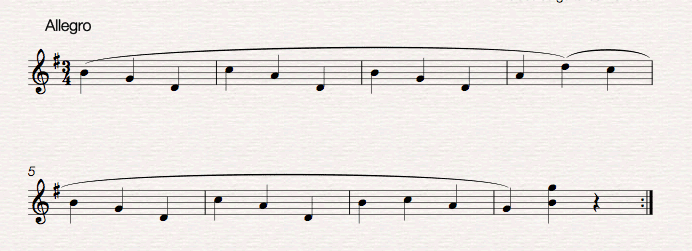

Let’s have a look at one by Carulli:

This example has two nicely balanced four measure phrases. The first phrase ends on a dominant harmony (the notes spell out most of the D7 chord in the key of G) and the second phrase finishes on the tonic chord of G major. This example is nice and balanced. In the classical style you will often find phrases that are two, four, eight, or sixteen measures long. These phrases can then be subdivided into other parts, but we will talk about them later.

Now, if we take the same passage of music, and consider the phrases to overlap one another, or to ‘elide’, then we get a somewhat different shaping of the music. In this case, the D and C lead back in to the next complimenting phrase and it give an almost up-beat effect. Both phrasings are ‘correct’ but they have different outcomes. And therein we find the wonderful world of phrasing and its possibilities. Just like the meanings of spoken sentences can be changed by commas, so can musical phrases have variation in meaning and cohesion.

Irregular phrases

As I mentioned, phrases can often be balanced, even quite symmetrical, but in other cases it can take some detective work to figure it all out. I remember a lot of chamber music rehearsals, especially with more complex 20th Century music, that dedicated discussions to agreeing on where the phrasing was. It really is an important thing to understand and decipher, it will make the music more sensical and enjoyable for both the performer and the audience.

Horizontal vs. Vertical Thinking

Thinking horizontally is something that doesn’t come very naturally to guitarists. But working on horizontal phrasing is the key to playing long beautiful melodies.

First let me clarify what I mean by the term ‘horizontal’. When we look at a guitar score that has chords and polyphony we will stack those notes in our head to think what chord that makes or how to finger them. That is thinking ‘vertically’. If we always think vertically, then we start marking the beats in each bar, even if it doesn’t suit the music.

Thinking horizontally is when you consider where the notes are going and where they have come from. If you have a clear idea of the whole melody you will play it quite differently than if you were reading it one note at a time. By analogy, it is like you had to read a speech to an adoring public but you were only given one word at a time on the teleprompter, you just wouldn’t know how to link each word, and shape each sentence. It would come out. One. Word At. A. Time. Vertical….

As I said, this doesn’t come naturally on the guitar partly because it is not a sustaining instrument and we don’t have to breathe to make the notes sing. So, the best way to get around this is to put the guitar down for a moment, and sing along! Even if your voice is not top notch (points at himself) you will still phrase more horizontally when you sing. Once you have graced us with your beautiful voice a few times go back to the guitar and play through the phrase trying to imitate your singing line. That is playing horizontally!

The bar line is not your friend

One more thing before you go.

Those rhythmic divisions between the bars, you know, the bar lines. Somewhere along the line you were probably taught that the downbeat, the “1” is the strongest beat in the bar. Well, it may be in a general way but it doesn’t mean that you have to accent every note in a melody that lands on the down beat. If you do, then the melody starts to be broken up into sections and that stops a phrase from being formed. So instead of playing all your lines as 1234,1234,1234,1234 take care to look at the phrasing and figure out where the accents will actually suit the music, rather than the bar lines.

The Sentence Structure

Phrasing in music is incredibly important, but it is also important to recognize the smaller sections of a phrase. These smaller sections will help you understand how to play a phrase, it will aid in understanding the composition and in the process of memorization. All in all, phrase structure is a very useful piece of information.

Sentence structure in language

Just as in written language, there are structures that appear over and over again. So much so that you could often predict the ending or at the very least know how to speak it out loud with the correct inflection and pauses.

Some examples of predicable phrases from a speech might be:

- Good evening ladies and gentlemen, it is my pleasure to be here this evening.

- I would like to thank my friends and my family, for all the support they have given over the past year.

- Thank you for your time and attention, I hope you enjoy the rest of your evening.

I think we could safely say that these phrases are fairly predictable, and even though you might not know what exact words are going to be used, the role these sentences play and their meaning are very familiar. Let’s parse these sentences to see what they are made of.

These three sentences are all quite balanced in that they have a comma breaking up the sentence at the mid point. Before the comma, there are two items addressed. In the first sentence it is the ladies and gentlemen, in the second it is friends and family, and the third has time and attention. Following the comma we have a sentence section that is equally as long as the first and it contains different material.

So, if we were to break it down into two sections, we could call the material before the comma “a” and the material after the comma “b”.

- “a” Good evening ladies and gentlemen,

- “b” it is my pleasure to be here this evening.

Let’s go ahead and divide the “a” section again because there are two subjects.

- “a1” Good evening ladies

- “a2” (Good evening) gentlemen

So, we end up with : a1 + a2 + b

Have a look through the other two sentences and parse them in the same way.

Sentence structure in music

So what would be the equivalent in music? Well, I am glad you asked. In common practice music we find sentence structure throughout the repertoire. The most common style that promotes this structure is the classical style, but it can be found in all other periods including the modern day. The example we will look at is from the very famous Minuet in G by Christopher Petzold (formerly attributed to J.S. Bach)

In the first two measures we are presented with the first idea. This essentially consists of some leaps in the melody and a short scale fragment in eighth notes. This idea is then repeated, but not exactly. The pitches have been transposed up, and the bass line is slightly varied. So, we can say the first two ideas are very closely related but there is some variation.

Therefore the first two measures can be identified as “a1” and measures 3 – 4 as “a2”. The phrase then concludes with a new idea that is four measures long. This is going to be labeled “b”. The general direction of the “a” section is rising in pitch and the “b” section is descending in pitch. In this way they compliment each other and create a nicely balanced phrase in sentence structure. The phrase is also balanced by the number of measures.

- “a1” = 2 measures

- “a2” = 2 measures

- “b” = 4 measures

2+2+4 = 8

And there you have it, the ever popular 8 measure phrase. Once you start identifying these sentence structures in music you will find them popping up just about everywhere. It will really change how you listen to music, and it can greatly aid in structured practice.

Pop quiz, hot shot…

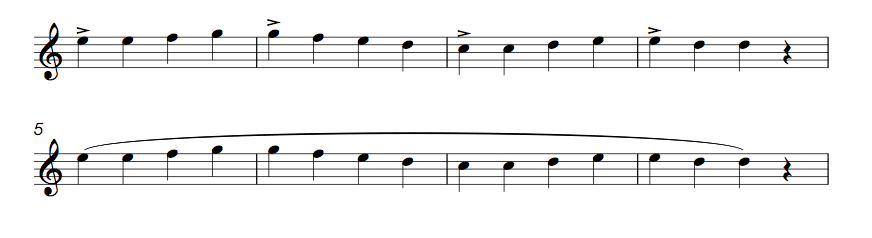

See how many examples of sentence structure you can find in this selection of excerpts. The excerpts are taken from my album Departure. Bonus points if you can name the pieces. Write your answers in the comments below!

Loved your article on phrasing. Such an important part of making a musical statement. I ask many of my students to sing the melody in a piece and note when they take a breath. They are surprised when they then play through even a simple piece and hear the difference.

Yes, the vertical approach is too often the beginning and end of instruction, as if this must be mastered before one can concentrate, and gain insight, from the horizontal view. Strange as the melody is in the horizontal flow. Great article.

Thanks, please write more articles like this one :)

When I started playing the guitar with folk music in the 60s, phrasing came naturally with the lyrics and chords were the music. Both horizontal & vertical were covered. But life got in the way & I stopped playing.

When I picked up the guitar again 20 years later, this time with an instructor, music became individual notes on the page. Again life got in the way. A few years ago I started playing again. Taking lessons for 3-4 months at a time when I was in one place. (I’m a snow bird; I travel a lot.) Just this past winter my instructor taught me to look vertically, to see the chords.

Simon, this article & its companion piece (https://www.classicalguitarcorner.com/classical-guitar-interpretation-guide-5-concepts/) are vital for turning notes into music. Thank you.

Beautifully stated and so obvious when you present these concepts in such a pedagogical way.

I wish my teachers had taught me about phrasing when I started studying music.

Thank you

Armando

I have to second this comment. We need to be taught phrasing from the beginning.

Venturing into pop music arrangements with a classical guitar will be a good comparison since we know the melodies by heart… we will take phrasing for granted. However, the objective of phrasing the piece properly remains a priority.

Thank you for sharing this excellent article with us.

Hi Simon,

i noticed your questions was not yet answered.

it is not so evident to name the nr of phrases exactly but this is what i heard and give it a try;

Mauro Giuliani Rossiana Op 119 opening — 5 Phrases

Ben Verdery Satyagraha-4 Phrases

Isaac Albeniz Majorca

Joaquin Turina Op 61 7 Phrases

Bach fuge BWV 1001-5 Phrases

Philippe Houghton 2 long Phrases

Mauro Giuliani Rossiana Op 119 — the end in 2 phrases

thanks

joannes

i forgot to mention Albeniz where i hear only 2 phrases but so much intertwined..not easy at all

Great article! Very helpful and clearly written, thank you so much for sharing!

Excellent! A new way to look at the pieces I play. Now to start working on my thumb to sing a different “voice” than my other fingers.

Interesting way of looking at music. I loved the comparison to sentence structure and how music can then have more meaning,

Thank you! Excellent teaching much better than master classes and much faster.

Perfect way to learn for aspiring classical guitarists.

Excelent explanation about horizontal phrasing!

Thanks for sharing.

I have enjoyed this article very much……. very easy to understand and it is something I can work on while my wrist is recovering…thankyou…Leonie

Thank you, Leonie. So glad that you found it useful!

Very, very didactical !!! Congratulations for the way you put it so clear !

I took classical guitar lessons at two different times in my life. The second teacher taught me about phrasing, including singing the lines as a practice method and as you say, it was eye and ear opening. Your lesson on the same topic is even more helpful for the breakdown of phrasing elements as well as the demonstrations.

Simon

your article was interesting. Although a novice your words clicked after I recognised the tune (the Minuet in G). This tune was

apparently used in the song Lover’s Concerto by a group called the Toys in 1965. Suddenly your topic became clear at least in this

case.

It may be more difficult with tunes I don’t know, but I’ll give it a “red hot go”.

Thank you Simon very helpful information and inspirational.

Thankyou Simon

I’ve sung for most of my life, so phrasing has probably come quite naturally – until I got on the guitar, when I was taught to learn chords, and their finger positions. Of course chords and harmony are completely relevant, but the melody is more so. I’ve only recently begun to understand that, when I’m reading a piece of music, I should be picking out the melody fingering first – in other words, your “horizontal”. Sometimes the “chord fingering” becomes a distraction, because I have to find a more efficient way of playing the chord, in order to suit the melody and phrasing.

Again, thanks for your article: it clarified the perspective.

I loved reading this article and hope to read more that give so much insight to learning more about the clssical guitar playing and listening. It was so very helpful in seeing things in a totally new way.