Your Guide to Polyphony in Music

Polyphony simply means “multiple voices.” In classical music this can range from two independent voices in dialogue with one another to the counterpoint of a baroque fugue. Polyphonic music was especially important during the Renaissance and Baroque eras, where the intricacy of voicing was at its height.

And there is a lot of polyphonic music in the guitar repertoire as well. While in other guitar genres chords are very important, in classical guitar music voices take precedence.

Ever heard a beautiful classical guitar piece that you could have sworn was two guitars, only to find out it was only one? That is the magic of polyphony or voices on the classical guitar. Check out a great example from the repertoire:

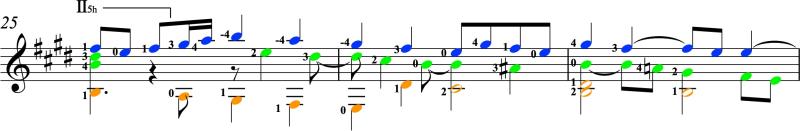

The Bach Bourrée, from Lute Suite in E minor (BWV 996), features two independent voices.

Polyphony, monophony, and homophony: What’s the difference?

Not all music features multiple independent voices. In fact, there is a lot of music that features either homophony or monophony.

Monophony

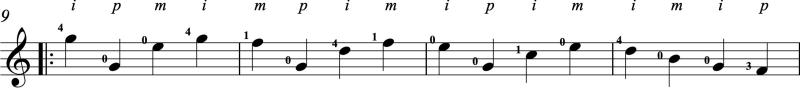

Monophony is a single-line melody. There are some great examples in the classical repertoire of single-line melodies. We even have some great examples in the classical guitar literature. Sor’s “Study 1” from Op.60 is a great example:

Homophony

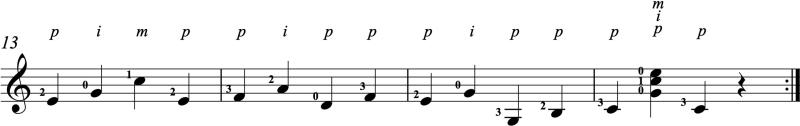

Homophony, by contrast, is a melody with accompaniment. Because the accompaniment just supplies harmonic support, it’s not actually made up of one or more independent voices. Again, there are many examples of this sort of texture in the classical guitar repertoire. Take “Adelita,” by Francisco Tárrega, for example, which is mostly a single melody with accompaniment.

Polyphony in Notation

So let’s look at how polyphony appears in notation.

Rhythmic Requirements for Voices

As a general rule, every voice must fill out all of the beats in a measure. Let’s say we are in 4/4 time signature. That means we have four quarter note beats per measure. While one voice may play on every beat in the measure, another voice may play only play for half the measure. Thus rests help communicate when a voice enters and stops.

Rests above or below Notes

For this reason we will sometimes see rests above or below notes. This might seem confusing at first. How do I play the note, but also the rest? But as soon as we break down voices in the piece we can see what the music communicates.

As we can see in the example above, we hold the D marked green for the full measure, four beats. But the upper voice rests for the first beat and doesn’t come in until beat 2. This helps to clearly differentiate voices in the music.

Stem Directions in Polyphonic Music

Another way classical guitar music differentiates voices is by the direction of stems attached to noteheads. While this is not always the case, most frequently a melody or upper voice will have stems pointing up. Bass voices will usually have stems pointing down. If there is also an accompaniment or third voice between the melody and bass, things get a bit more complex.

Here’s an example from the Waltz by Ferdinando Carulli:

Shared Noteheads in Polyphonic Music

In some contexts two voices may share the same note. In these cases, the voices will share the same notehead with two different stems. Here’s a great example from Sor’s “Study No.9,” Op.60:

The notehead will still be solid for quarter notes and shorter, and hollow for half notes or dotted half notes.

Polyphony with more than 2 Voices

Things get a bit more complicated when we have more than two voices present. Take this example from John Dowland’s “Fantasia P1a,” for instance:

A fourth voice is often present in this piece and is even implied in the above, but we have colored three distinct voices for clarity. Notice in this case that both the middle and lower voices have stems going down. Moreover, at times these two voices share the same stems! Knowing which notes belong to which voice requires knowledge of the style, voice leading, and range of voices.

Implied Polyphony

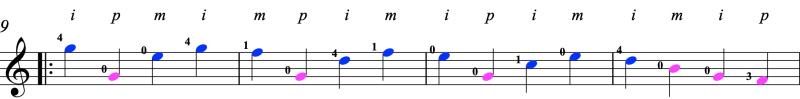

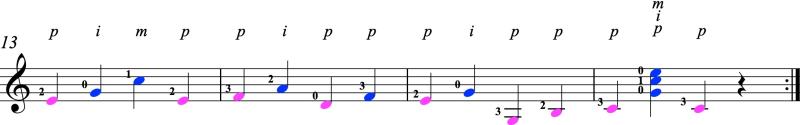

Sometimes polyphony may not be explicit, but is only implied within the texture. It can be very challenging to recognize distinct voices when we only have single-line melodies. J.S. Bach was the master of implied polyphony and it’s something you will encounter in his solo violin and cello works. However, we can see it at a much simpler level in one of Fernando Sor’s beginner studies. Let’s look at the B section of Study No.1, Op.60:

If we play it exactly as it’s written, it doesn’t sound quite right. For instance, if you only hold every note for exactly one quarter note it sounds detached. Something’s missing. And what’s missing is voicing. So let’s now look at where implied voices are present:

Now if we allow the blue notes in the first line to connect with one another by holding them down longer, they make a clear melody. Likewise, if we hold and connect the pink notes starting at the end of measure 12 together, they form a bass melody. If you play it this way, suddenly the piece comes to life.

Voice Independence in the Right Hand

Now that we have a better idea of how to identify and differentiate voices in our classical guitar music, how do we use this in our playing?

Perhaps you have had a teacher who has asked you to “bring out the melody” in a piece better. Or maybe you played “Lágrima” by Tárrega and realized the open second string in the first section is distracting. These are elements of voicing.

Allowing the melody to be more prominent than the accompaniment is a matter of voicing. Making sure the open third string isn’t too loud in the first line of Sor’s Study 1 above is all about voicing. And we control voicing on the classical guitar with our right hand.

Playing Polyphony with Right-Hand Weight

One obstacle to clear voicing in the right hand is a lack of independence between right-hand fingers. We tend to be pretty heavy with the thumb and the ring finger and this causes unwanted accents in our music. So what we have to do to train independence in the right hand is to learn to give weight to different fingers, one at a time.

And a great way to do this is to repeat an arpeggio and each time bring a different finger out. In order to bring out that finger, allow it to have more weight, to press slightly in toward the soundhole. As you do so, focus on making the other fingers much lighter. Now try switching to a different finger. Once you’ve mastered doing this with simple repeated arpeggios, you can switch to trying the same thing with block chords. This is much more difficult, especially for the inner i and m fingers.

To get started with right-hand weight, check out Exercise #2 in our 7 Best Exercises for Classical Guitar.

***

We hope this lesson has been useful for you on polyphony in music. Learning to add voicing to your music brings a whole new dimension to it. Ready to make your music more, well, musical? Go check out 7 ways to create a musical interpretation.

Great information Simon, will need to try with the pieces you included.

Thank you so much