by Dave Belcher

Five years ago I was accepted into a doctoral program in theology and liturgy at a seminary in New York City. I was very excited about the opportunity and moved my whole family from North Carolina to live in a very different environment up in Manhattan. That process lasted a month before I had to withdraw from the program — that is a long and much involved story I won’t get into here. But the long and short of it is that the difficulty of that whole process led me back to the classical guitar after a pretty long break and ultimately planted the seeds for an idea of bringing these two worlds together in my own life: spirituality and music.

So for the past four years I have been reflecting on ways that I can connect these two important parts of my life and this has led me to explore what I have been calling “sacred music” for the guitar. Now, I should clarify immediately that I do not mean “sacred music” in the traditional sense. Music is as ancient as human culture. Some of the earliest human cultural artifacts are musical instruments and as long as culture has existed, at least so far as we know, so has music. Likewise, the earliest religious gatherings (another essential and ancient part of human culture) have been accompanied in some respects by music. And this is an important point to make because the history of music in the West — and so what we know today as “classical music” — has been inextricably linked with the history of the Western Christian church. “Sacred music” in the traditional sense is the typical way of referring to that relationship and specifically the kinds of music that have been composed and used for religious ceremony.

So when I speak below about “sacred music” for the guitar you might be excused for thinking that I’m referring to this more traditional definition of sacred music, that is, music written for (often Western Christian) worship to be performed in specific ritual or liturgical contexts (and usually for either voice or organ). Instead, what I would like to talk about in this article is something much looser and open. But even if we were talking about what is traditionally understood as sacred music, you could equally be excused for thinking that sacred music and “guitar” don’t really go together. Sacred music has traditionally been associated with the voice (and choirs more specifically) and the organ, whereas the guitar has been a much more marginal instrument in most of the history of Western Christian worship whose introduction into worship music in the mid-twentieth century is often associated with decline and watering down more traditional sacred music.

In contrast to this more traditional definition, sacred music for the guitar was something that I began to piece together from a much wider and unexpected set of sources: “prayers” by composers such as Mertz, Tárrega, Barrios, Ponce, Segovia, Hand, Bartlema (and more!); reimaginings of medieval plainchant as well as variations and modern takes on Eastern Orthodox Christian chants; Jewish songs; modern chamber works for unusual (or underutilized) instrumentation such as guitar and organ or guitar and choir; Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic, modern, and contemporary sources; in short, I began to encounter a vast array of music that either worked with specific sacred source material (such as medieval Western or Eastern Orthodox or Jewish music) or had a spiritual theme of some sort in the title.

What I discovered as I began to piece together concert programs and even to perform some of this music was a fascinating convergence of worlds. On the one hand, it is quite interesting to see prayer and spirituality at work in music meant for the concert stage (and not for worship), that is, in the wider world outside of churches, monasteries, temples, synagogues, mosques, and prayer closets. On the other hand, a substantial venue for classical concerts today is churches, so there’s also an interesting interplay happening where a “sacred” space is being put to a more “secular” use, and so performing these “sacred” works in such spaces has some interesting connotations.

So let me walk you through a program I performed last year. First, here’s the program in full (and below that I’ll simply write out some of the talking points I use to introduce the pieces in concert):

⦁ Meyerbeer, Der Prophet, arr. Mertz

⦁ Castelnovo-Tedesco, No Hubo Remedio

⦁ Astor Piazzolla, La Muerte del Angel

⦁ Frank Wallace, Cunctipotens Genitor

⦁ Manuel Ponce, Variaciones sobre un tema de Cabezón

⦁ Steal Away, trad. spiritual, arr. Denis Mortagne

⦁ Simple Gifts, trad. American, arr. Fred Hand

⦁ Amazing Grace, trad. hymn, arr. Ben Verdery

Now you may be surprised to see some names here that you wouldn’t normally associate with “sacred” music (and especially Western Christian sacred music). For instance, Giacomo Meyerbeer was Jewish — a fact that was made very public in Richard Wagner’s terrible mocking of his former patron in print. Despite Wagner’s criticism, Meyerbeer’s Der Prophet, a sprawling Germanic opera, was one of the most important of his time. It featured a young Anabaptist reformer named Jan of Leiden and the tragedy that ensued among Catholic and Anabaptist conflict in the Netherlands in the sixteenth century. J.-B. Mertz’s arrangement for guitar pulls from some of the best musical moments of the opera.

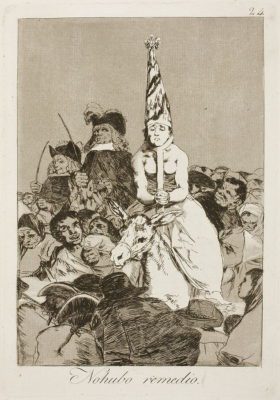

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco  was of course also Jewish. However, he took a broad interest in Christian music and ecclesiastics. “No Hubo Remedio” comes from his Caprichos de Goya, which are musical accompaniments to Franceso de Goya’s famous Spanish nationalistic etchings, Los Caprichos. In this particular etching Goya depicts a woman who has been condemned to death. She is wearing a dunce cap and is being paraded by her accusers through an angry mob to her demise. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s musical accompaniment is in the form of a passacaglia with seven variations and takes as its theme the famous “Dies Irae” (the Day of Wrath), which is a thirteenth-century chant from the Requiem Mass in the Western Catholic church depicting a day in which the world will dissolve into ash.

was of course also Jewish. However, he took a broad interest in Christian music and ecclesiastics. “No Hubo Remedio” comes from his Caprichos de Goya, which are musical accompaniments to Franceso de Goya’s famous Spanish nationalistic etchings, Los Caprichos. In this particular etching Goya depicts a woman who has been condemned to death. She is wearing a dunce cap and is being paraded by her accusers through an angry mob to her demise. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s musical accompaniment is in the form of a passacaglia with seven variations and takes as its theme the famous “Dies Irae” (the Day of Wrath), which is a thirteenth-century chant from the Requiem Mass in the Western Catholic church depicting a day in which the world will dissolve into ash.

Astor Piazzolla had no real religious background and has been described as agnostic. His tango “La Muerte del Angel,” however, borrows thematic material from the play for which the piece was originally written by Alberto Rodriguez Munoz called The Tango of the Angel. In the play an angel comes down to a barrio in Buenos Aires to bring healing to broken human spirits [spoiler alert] only to die breaking up a knife fight. Toward the end of the play, one of the characters described the angel as “an angel we created out of the fury of our impoverished dreams. A true angel, not an angel from God, who is in the heavens, so far from this squalor, but an angel that was ours, made by our desires, birthed by us.” Those who are familiar with Latin American liberation theology may see parallels in this description by Rodriguez Munoz.

Frank Wallace is a gifted guitarist, singer, and composer from New Hampshire. While he may not fit in the traditional category of “sacred music” composer, I feel much of his music belongs in that realm. “Cunctipotens Genitor” comes from a twelfth-century manuscript at the church of St. James at Santiago de Compostela in Northern Spain. It is an example of one of the earliest types of musical polyphony known as organum (and more specifically mellismatic organum). This particular chant is an elaborate, ornamented “Kyrie” chant. The Greek Kyrie eleison has been a central part of the Christian liturgy in both the east and the west from very early on and is a prayer for mercy in the face of sin. Frank Wallace’s composition is a modern fantasy on the chant and weaves in and out of various keys, deepening the polyphonic texture, before building to a rousing finale.

Manuel Maria Ponce was a devout Catholic and while “Variaciones y Fughetta sobre un Tema de Cabezón” does not bear a specific sacred title or theme, Miguel Alcazar, biographer and editor of Ponce’s Obras, has identified the theme of Ponce’s piece not as one of Cabezón but as the popular fifteenth-century Easter hymn O filii et filiae (“O Sons and Daughters Rejoice”). This hymn has been described as “The Joyful Canticle” and in Ponce’s hands proceeds to a set of variations typical of Ponce’s modern musical language before ending with a lively Fughetta.

The last three arrangements are all American hymns from different traditions. The first is an African-American spiritual called “Steal Away to Jesus.” It has obvious religious meaning, but it is also one of a handful of songs that bore secret instructions to slaves escaping on the Underground Railroad. This arrangement was made by French guitarist and composer Denis Mortagne. “Simple Gifts” was a Shaker tune written by Joseph Brackett around 1848 and was popularized by Aaron Copland’s majestic arrangement in his orchestral suite Appalachian Spring (1944). Fred Hand’s arrangement for solo guitar bears the clear influence of Copland’s masterpiece. “Amazing Grace” almost needs no introduction, though some may be surprised to learn that the origins of the song are not as clear as the impact the song has had in American religious and cultural life. While the words were penned by a former-slaveholder-turned-priest — whose conversion to Christianity drove him to become an abolitionist — the music is of unknown provenance. Renowned soprano Jessye Norman theorized that it could have been written by a slave and I really like the idea of that convergence of a slaveholder-turned-abolitionist composing lyrics joined with the music of a slave in this music of freedom. This arrangement was made by Ben Verdery on the occasion of his father’s passing and then later he added a darker middle section in honor of victims of the tragedy of September 11, 2001.

****

Thus, while some of this music converges with traditional sacred music, some of it is also quite external to that tradition. Ultimately I have been really pleased with responses from both so-called “secular” and “sacred” audiences when I have performed this music and my goal of bringing these worlds together has been surprisingly welcomed by both kinds of listeners (and others in between).

So if you have an interest in intersecting disciplines and worlds and would like to connect the classical guitar with not only spirituality (of which there are many varied and vast examples!) but also with other elements of cultural life — perhaps film, poetry, or visual art — I encourage you to dig in to the deep, wide, and open world of the classical guitar repertoire . . . you may be surprised at what you find.

Thank you Dave, your exploration of spirituality in music is poignant and a worthy path to pursue. Our musical excursions may not make sense yet are in keeping with our predecessors—-music is a way we seek to communicate with worlds unknown.

Thank you for the thoughtful comment, Drew!

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Hi Dave,

Though I’ve heard much of this from you before, it was great to be able to read through slowly..I missed a lot when listening. When Richard Croad was curating Reginald Smith Bridle for the Composer of the Month club, he assigned me De Angelis (from a plainsong) which has become one of my all-time favorites, and is also quite easy to play!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1T6rIy2j6zg

Thanks again,

Mark

Thanks for the nice note, Mark, and for sharing the De Angelis! I actually know the (plainchant) tune well but I hadn’t heard Smith Brindle’s take on it until I saw your recording at the Academy. There’s so much to explore in the classical guitar repertoire! Best wishes to you.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Hello Dave,

Thank you for sharing your ideas and music with us.

your ideas and music are worth exploring and contemplating upon.

We like to explore and put meaning into our music, your suggestion to explore the world of classical guitar repertoire has brought me to study The book of Preludes by David Pavlovits.

I feel deeply touched by his music but has never heard about this composer before.

How did you choose your music for your concert?

Did you choose the music that fitted your concept? or visa versa

This is maybe not the place for a discussion however i want to share my comments with you as you so well explained your ideas and brought new ideas to be inspired.

Thanks

regards,

joannes

There is a sad premise within today’s church communities that you can only play sacred music on a keyboard. I have lost work many times to really bad musicians who can only bang out block chords too loudly. I can illustrate how my fretboard can easily cover the same score. I can play most piano scores note for note. To no avail.

Thank you, Dave, for this insight both into what influences your playing and also for providing knowledge to a guitar neophyte. Although I am much more advanced in piano and also sing in choirs, I’m always looking for more information about the music that we all play.

Thank you,

Reg

I was intrigued and inspired by this blog. I know I will be pondering the interplay between the sacred themes found in music meant for the concert stage and secular music played in sacred spaces. It moves me to a place of awe and wonder. On a selfish note, I am hoping these recording bits are part of a full recording. If not, might I ask that you consider producing a recording of these pieces?

Hi Dave,

Read and enjoyed this article today. I believe that music has a connection to the human spirit that transcends any specific religious tradition, and therefore very much appreciated your perspectives on this topic and your sharing of this journey (and your performances),

Thanks

Nels

I came across another Shaker tune recently which greatly intrigued me, and decided to delve into Shaker history – knowing nothing about them other than hearing vague references to ladder-back chairs – and learned that in their heyday they produced a vast amount of music for song and dance.

The piece I came across was arranged for guitar by William O Bateman (1825-1883), a sometime lawyer, guitarist, composer and guitar teacher. Titled ‘The Spirit of New Lebanon’, it celebrates the pre-eminent position of that town within the Shaker community. I think it’s a fascinating piece, full of grandiosity but also moments of timorousness and questioning, and to my uncultured ear takes a lot from the idiom of folk music. For anyone interested in hearing a rendition of it, see this link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NxqmXFytsjs

Thanks for sharing that, Helen! That’s not one I was familiar with.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Hi Dave – I recently started learning classical guitar. I quickly realized the commitment to the instrument, and began to lose focus on many other things that are important to me. I was listening to Ana Vidovic driving in my car today, and was just blown away. I was thinking “she will be my inspiration to my purpose of learning and playing classical guitar.”

Then the thought occurred to me that I was almost completely ignoring my spiritual life (as a Christian) and started having double-mindedness. I decided that when I arrived home, I would research how I may fuse CG and my Christian Faith together (if such a thing even existed!) . I didn’t take long to find your blog, so, thanks to you, I can now serve a holy purpose!

Blessings to you, sir!

Vince

Thanks for the nice note, Vince! Very happy to hear my article was helpful for you. Best wishes.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

What a beautiful exploration! I know this is a couple of years old at this point, but I’m trying something similar and wanted to ask for suggestions. I’m planning on recording a CD of guitar music inspired specifically my mystical stories or experiences in Chriatianity. So not so much coming from hymns from the church’s past, but born out of the mystical experience.

So far I’ve found Asencio’s “Suite Mística,” Mompou’s “Suite Compostelana” (inspired by the story of Saint James), and Barrios’s “La Catedral,” allegedly inspired by a religious experience he had. Any more that come to mind for you?

Thank you so much!

Aaron

Hi Aaron,

Glad you enjoyed the post! It’s a fun topic and the answer to your question is pretty big, I think. Those are wonderful pieces, all ones I’ve performed in the past (Mompou has some wonderful “sacred” music for piano as well, like Musica Callada written after St. John of the Cross.) Maybe could you shoot me an email and I can offer some suggestions? Best wishes to you on your recording project! [email protected]

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Hi Dave

I just came across this for the first time (shame on me!). I find your music to be intensely spiritual and I enjoy it immensely. I have a question: for our in person meetup in a church next month we have been asked to play religious/spiritual music. I don’t have any that I can play right now, so I’m wondering if you have suggestions for a fairly easy piece – I am immersed in several pieces that are testing my abilities so don’t want anything too challenging! I think a number of potential attendees would also be interested.

Hi Julie,

It can be difficult finding good, more approachable “easy” sacred music pieces as a lot of arrangements of hymns and other sacred tunes are quite involved. However, my favorite set (which most wouldn’t count as “sacred” music per se) is the collection “Six Prayers for Six Strings” by the late Frank Wallace. Number one will be the most approachable. The most challenging piece is one that requires you to cut out an eraser to use as a special string tool (the syncopated rhythms require a lot of coordination)…but I can show you what I came up with in conversation with Frank if you’re interested in that. You can listen to the composer’s beautiful performance of the six prayers here:

https://gyremusic.com/products/six-prayers-on-six-strings/

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Thanks Dave for sharing this text. Soli Deo Glori

This is a great article!

I can clearly see a set of method books for classical guitar sacred music, inspired by some of the great music brought forth by community members.

Thanks for the nice comment, Tony.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

I would be very interested in hearing more about your conversation with Frank Wallace.

Raphael Scarfullery has a set of 10 pieces called Prayers for the World. Some are quite good. Probably around grade 2-4, not sure.

Thanks, Tony! I believe I had seen some of Raphael’s hymn arrangements, but I hadn’t seen those pieces. Very helpful. And sorry I missed your earlier comment. Frank showed me how to cut out an eraser (and what kind of eraser to use) for creating the sound he gets on “III. Reverence” from Six Prayers for Six Strings. Best wishes.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

I forgot to mention I had found another source of simple hymn arrangements for classical guitar by Kimmy Kwong. She has a YouTube channel with plenty of videos.

This might be helpful to some CGC members.

Hi Dave … a question. Do you have arrangements for hymns, masses, etc. for classical guitar … intermediate or higher? Thx Greg