Scale practice on the classical guitar is probably the first thing that comes to mind when we think of practice and technical development. The idea that practicing scales makes you a better musician seems to be universally accepted yet in the case of the classical guitar the concept of scale practice seems a little misunderstood.

Before I get to the big mistake people make, let’s have a look at why scale practice is so useful.

Would you like a free classical guitar scale book to go with this lesson?

Benefits of Practicing Scales on the Classical Guitar

Scales on the classical guitar combine several elements of technique into one process.

- Right hand alternation

- Left hand shifting

- Left hand independence

- String crossing

- Tone production

- Rhythm

- Speed

- Dynamics

- Articulations

- Fingerboard knowledge

And the list goes on…

In fact, out of all the exercises you might use on the classical guitar, scales provide the most efficient synthesis of technique. It is that synthesis that is so special and it it something that we don’t always find in other exercises.

Scales can provide almost all of the technical challenges found in repertoire but they allow us to work on individual elements away from the music. In this process we can prevent ourselves from treating pieces of repertoire in a “technical” or “mechanical” manner.

The big mistake

Scales occur frequently in music written for violin, flute and piano but they rarely appear in the guitar repertoire.

A full octave scale is actually quite hard to come by in much of the literature and when there is a long scale passage in a piece of repertoire, it stands out partly because it is so rare. Examples include the Concierto de Aranjuez by Rodrigo, Capricho Arabe by Tarrega, and Fantasia para un Gentilhombre again by Rodrigo.

Another famous example is the Bach Chaconne, however, this piece was originally written for the violin.

Violin and piano repertoire is absolutely littered with virtuosic scale runs that span genres from the Baroque to the present day. So it makes sense for those instruments to incorporate scale practice into their routine for the sake of repertoire demands.

For us, though, it does not make a lot of sense to practice scales in preparation for the occasional scale run that pops up in a piece of repertoire.

So why do we practice scales ?

Scales are tools.

They are simple frameworks that we can use to hone in on specific technical elements. Once those elements have been worked on in isolation they can be incorporated into music making, which is the ultimate goal of any technical work.

Without a specific focus to practicing a scale then the time is wasted without any goals being reached. The scale itself may become familiar and fluid but seeing as there are few actual applications of a scale in a piece the process really is, pointless.

Goal Oriented Scale Practice

Using goals in scale practice allows us to divide our focus and more easily manage different musical elements one at a time.

One goal might be to practice crescendo and diminuendo another could be to practice staccato articulations yet another is a variety of rhythms.

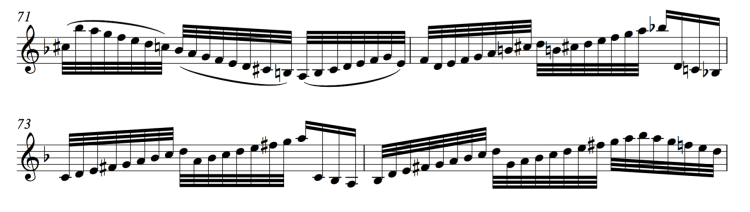

Here is an example of a scale incorporating dotted rhythms and crescendo/diminuendo:

Scales can provide a blank canvas for working on so many different technical or musical elements, like:

- Right-hand alternation

- Synchronization of the two hands

- Left-hand shifting

- Dynamics

- Tone Color

- Alternative right-hand fingerings

- …and more

But that’s a lot to manage all at once. Thus, in order to get the most out of your scale practice, it’s important to practice with a goal. Goal-oriented practice with our scales allows us to focus on each of these different elements in isolation and develop them more easily.

The ways to use a scale to work on technical aspects is almost as diverse as your imagination and to inspire you I have created a video that splits up scales into five levels, each with different focus areas. You can watch that here:

And here are some more specific examples of technical aspects you can use in your scale practice:

Alternation with “p i”

One example of a specific way to use scale practice is to develop fluency in different right hand alternations. More often than not we use i and m in alternation and they have proven effective for many people. Other finger alternations can have specific sounds, speeds and articulations so it can be worth your time to investigate other options. If you would like to use the free scale book to accompany this lesson, please feel free to Download Your Daily Scales Now

The pi combination is very clear and articulated but it can also sound a little staccato on the treble strings due to the opposing direction of the thumb and finger. One solution to this is to use a combination of p-i and i-m. Use p-i for the basses, and i-m for the trebles. Personally I find this combination of fingers incredibly useful. It balances the hand and it is accurate and fast.

One issue that might arise is the natural tendency of the thumb to be louder than the finger, giving the notes played with the thumb a bit of an accent. To combat this, try practicing some scales with accents on the index finger, with goal of obtaining an equal volume and sound quality for each digit and a smooth transition between i m and p i. Accenting individual digits will also help you practice any sting crossing issues that come up. Of course, if p-i isn’t your cup of tea you can try p-m, or p-a. It really depends on what works best for you, because in the end, we are all individuals. (If you are up for a challenge try p i m.) If you have your own combination that you would like to share please leave a comment and let us know!

Left Hand Pressure

In a similar way of focusing on a very specific aspect of technique we can work on left hand pressure through “buzzing” scales:

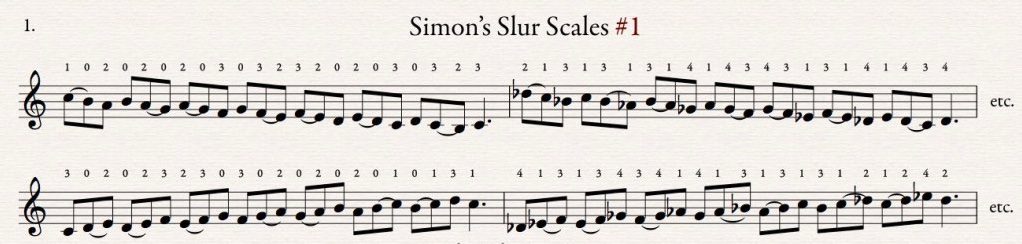

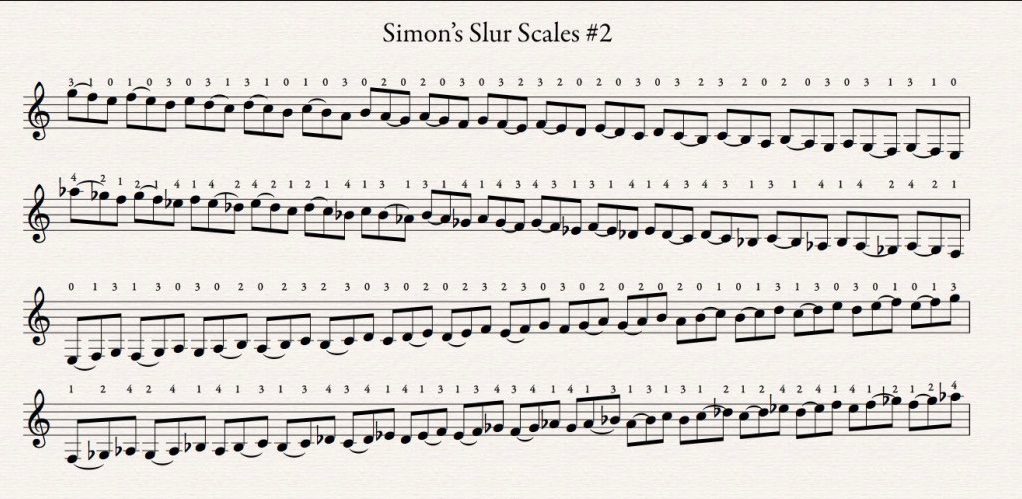

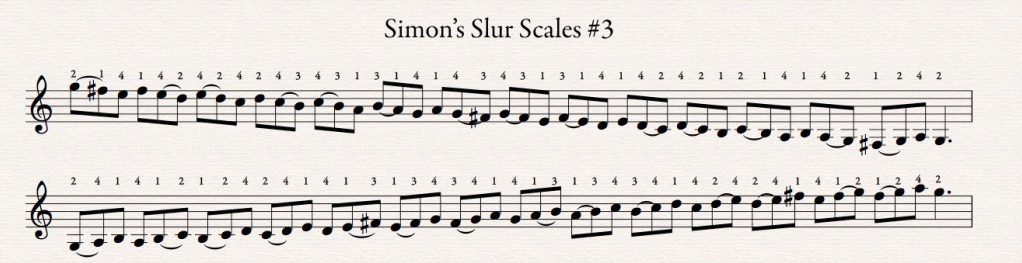

Slur Scales

Here are some slur scales that come from 20 Practice Routines for Classical Guitar.

You will notice that the scale takes on a pattern (except in first position) that can be repeated. Once you have completed one slur scale, shift the pattern up one fret and repeat the process. Be careful not to wear your hand out because slurs can be very tiring on those weenie left hand muscles and tendons. If you only want to do a few light repetitions you can start the patterns higher up the fretboard, around the seventh fret, as it will be easier than playing down in first position.

Focus on making a clean, crisp slur with a consistent snapping motion. After a while you will find that these scales start to flow nicely, at that point go and impress your girlfriend/boyfriend/attentive pet with your snappy slurry scales.

If you have some scales or exercises you like to do, let me know and we can share it with everyone.

an extension of the first shape…

a new pattern, you may recognize me from such books as “every scale book ever written“

An extended list of practice goals for scale work

Here are some suggestions on how to apply goals your scales:

Dynamics

- Crescendo / Diminuendo

- Terraced Dynamics: pp,p,mp,mf,f,ff

Rhythms

- Dotted Rhythms

- Triplets with duplets

- Groupings of 5,6,7

Tempo

- Accellerando

- Rallentando

- Lento, Andante, Allegretto, Allegro, Presto etc.

Tone Control

- Ponticello

- Tasto

Extended Techniques

- Pizzicato

- Harmonics

- Slurs

Articulations

- Stacatto

- Legato

- Tenuto

- Sforzando

- Accents (place accents on different notes)

Right Hand Fingering

- im, mi, ia, ai, ma, am, ami, mia, ima, pima, amip, pi, ip etc.

Left Hand Fingering

- Shifts

- Fixed fingers

In Summary

Scales are fantastic. They combine many elements of the left and right hand techniques and we can add infinite variations to cater scale practice to our specific needs. Just be mindful of the common pitfall; mindless practice of scales that go up and down without any thought or purpose.

Use them as tools to hone in on technical or musical issues.

Be very specific as to why you are practicing a scale. Speed, sound, accuracy, articulation, dynamics etc. these are all techniques that can be worked on with scales. As I said, the classical guitar repertoire doesn’t actually have that many large scale passages, so simply practicing a scale to be able to play that scale has little use in music making.

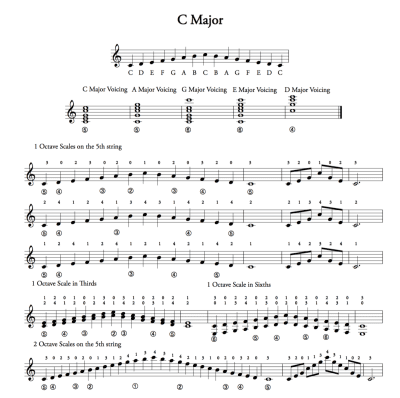

Your free scale book

In the scale book that I have written I aimed and providing sound fingering that will instill a logical manner to move around the fingerboard. In addition I took great care to structure the scales in a systematic way that would aid the student in acquiring fingerboard knowledge and also understand how scales relate to chord shapes.

If you would like to use the free scale book to accompany this lesson, please download a free book of scales to practice every day.

Simon

The scale practice is good only when a player wants to learn a new piece with a scale in it. Sometime, I found it is good for warm up purposes and technique practice.

I have been playing since 13 years of age. Every Saturday I trekked uptown with guitar in case (a Stella $12 guitar) spent 30 minutes with an instructor for $3.00. The man was a poor teacher as have been my encounter even to the University level. I cannot play worth a crap. Now I am 70 and still learning an playing like crap. My mind is going because I cannot seem to get a 2 page piece memorized, and I have never known what to do with scales because all my instructors have never explored the importance and value of scales. David Patterson arrangement of Czerney for Guitar, a 12 scale study for classical guitar has been wonderful. I am still struggling with understanding scales. This site has finally exposed what I need to work on. I also indulge myself with Francisco Tarrega’s complete technical studies, which has been interesting. I once had Bach’s Cello suite No. 3 memorized, now I cannot get past the first page of the Prelude.

Hi Tom,

I am so glad that I can offer at least one “penny drop” in your learning experience. I also struggled to find a good teacher for several years when I started the guitar, and I can understand your frustration.

In regards to memorization, I think that is an option and some are more adept than others. For myself, I have decided to develop my reading skills and use scores in performance. It is a lot less stressful, and less time consuming!

Simon

Simon,

Thank-you for this statement! I had sets of classical guitar music memorized about 30 years ago. I had a vision that all these pieces were spinning out of control in my head and had to be removed. Well, it happened, they are gone. I have continuously sight read every piece of classical guitar music that I can get my hands on since this incident. I used to feel that sheet music was a crutch for my poor memory but now I believe it is a disservice to the composer not to study it AND have it present when their piece is performed. As one of your admirers, I am proud to agree with you! Keep sight reading!

I wouldn’t fret (ha) about memorization. You are internalizing the music with out you being aware. It is very similar to typing on a keyboard in that sense. I know what word I want to say, but what word and what letters I use to make those words can be interchangeable and there are a variety of equally correct solutions.

i/m alternation rhythmically accented in groups of 3: i m i, m i m, etc. Similarly with m/a and i/a. Also, i/m/a or a/m/i in rhythmic groups of 2 or 4. I love scales, they are like old friends.

Consider hijacking a jazz approach to scale and arpeggio practice. “The Serious Jazz Practice Book”, by Barry Finnerty is at the top of the list. The author is a guitarist, but the book is not specific to guitar. This book demands much. It does not take the usual mindless approach of “monkey see, monkey do” to scale patterns.. Many of the starting exercises are in the key of C, but don’t let that fool you. You are supposed to transpose each to all keys and positions. You are also supposed to integrate ear training in each of the exercises. Now integrate solving the right and left hand issues as in this article’s excellent exposition. You will be a monster player. No kidding.

Great suggestion, Michael! Thanks for the comment.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

I’ve said this a thousand times, if I’ve said it once. Before ALL else, rhythm is the most important aspect of music. It is the foundation of everything. Without timing, you have have nothing. Notes,intervals chord inversions etc. you can learn. Rhythym you have to feel. What good is knowing scales,chords etc. if you can’t play in time. Very little music is rubato. Be able to tap out rhythmic patterns on anything, while carrying on a conversation. Make it part of your DNA, everything else comes after.

what is i m a m i a .?

i’m self taught in alternative tunings. i took many lessons in standard tuning but found i couldn’t get close to any songs. so i ventured off into no mans land with alternative tunings and finger picking patterns i have come up with. pretty much i know zilch about music but enjoy transposing the voices in my head to my guitars.

seems as though everyone who wants to teach me guitar is so far out of my league using terms that are greek to me and “now do this”. even when i tell them to start from the very beginning as if i was 5 year old,, no one explains how why or how come.

Hi Rick, I hear what you are saying, and perhaps you will find what you are looking for in Beginner Lessons on the lessons page.

Excellent lesson Simon

Opens up the Scale World like no other presentation on this subject before.

Many thanks

Robt

Simon, I struggled for a long time about the importance of scales. Your lesson is a real eye opener and has opened for me a new impetus to start afresh, and to begin to use these to build better technique and site reading skills.

I have enrolled for the courses. For the first time I am no longer looking at myself simply as someone who can play the guitar but look at myself as a musician who wants to improve.

Thank you

Keith

Scales carry the keys that unlocked the doors of music for me!

That’s great to hear, Michael! I hope Simon’s approach above can continue to help.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

What is your opinion on the Segovia Scales? I am practicing stretch scales over five frets and up to the third octave on the first string. I play the basic modes in one finger per fret in position.

Could you please demonstrate a scale of Eb which uses all the open strings? It comes out quite Ea stern, with two E’s.

I’ve not got arpeggios for this, nor chords, but I can’t help think that if we have the scale then this transformation is in classical music theory. Given that there are likely to be consecutive semitones in the scale, the derived chords away from the root could prove rather more interesting.

Using them in a classical framework could produce some unique sounds.

Scales on the guitar, especially longer scales, are extremely difficult when compared to other instruments. This is probably why they are relatively rare in guitar repertoire. BUT SCALE PRACTICE IS ESSENTIAL FOR SERIOUS GUITARISTS. Why, because they demand excellent technique from both hands. Most guitarists do not practice scales enough! Bad practice habits applies to everything not just scales. Arpeggios, tremolo, slurs etc can also be a waste of time if not practiced correctly. Scales are nothing different. The quality of one’s technical practice is important across all aspects of technical development. I’m not sure why practicing scales is usually singled out. Scale practice is exceedingly important. When I see a student for the first time, I can immediately tell his playing level by asking him to play a 3 octave scale and tremolo. Most guitarists need More scale work, since they involve fundamental aspects of playing.

Thanks for the comment and your helpful thoughts, James!

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

I’m sorry but I don’t know where to start with the scales. It appears I obviously must know how to read the music in order to play the scales correctly.

Hi Jeff,

The numbers above the notes will tell you which finger to use (0 for open strings, 1, 2, 3, 4 for index, middle, ring, pinky). The circled numbers below the strings tell you which strings to play the note on: beginning on the fifth string (the second lowest/thickest string) all the way up to the second string (the second highest/thinnest string). Now, imagine that each of your left-hand fingers is assigned to a fret: the first finger is assigned to play only notes on the first fret, the second finger only notes on the second fret, the third on the third fret, and the fourth on the fourth fret. Now put everything together: the first note has a 3 over it for the third finger (so we’ll play this on the third fret), while the circled number below it tells us to play on the fifth string. That note is a C. For now it’s not all that important to know each of the notes you’re playing: learning to read notation takes time and discipline.

But this should be a great start and will get you playing your first scale! Let us know how it goes.

Peace,

Dave B (CGC team)

Thank You

Appreciate the lessons

and the completion

more to think about different combinations

Enjoying your lessons. I have a one of a kind Zen-on Japanese made classical guitar. It’s about 50 some years old. It’s in good shape. Must be worth a few Yen or bucks. To me, it’s my go get guitar when I’m drinking sake . :)

Can somebody please explain a ‘scale passage?’ I am teaching myself classical guitar and I know that scales and scale passages use the ‘Rest’ stroke. Does this mean that if you’re playing a piece of music and it has 2 or more consecutive notes going up or down that you use the ‘Rest stroke?

[…] with scales, these right hand studies can be built upon by teacher and student to refine musical aspects such […]

[…] This lesson comes from our brand new Scales & Arpeggios course. The new course features 40 lessons in total and is structured in a progressive way to help you develop these important building-block techniques step by step. Want to see a sample scales lesson? Go here to see a lesson from the new course on scales. […]