Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

How to develop speed in the right hand

In this article we’ll look at how to develop speed in the right hand.

For whatever reason we always want things we can’t have. The classical guitar excels in producing soft, dulcet tones. So, therefore what do players want to do? Play loud and fast!

I have dealt with the topic of playing loud on the classical guitar in another post, so in this post we will discuss the topic of right hand speed.

Playing fast on the classical guitar is relative. The very fastest players will be overtaken with ease by electric guitar players using a pick, and in turn our electrified colleagues will get overtaken by violinists, pianists, and flautists. Even still, it is hard not to be thrilled by a player that exhibits speed coupled with fluidity and volume.

Let’s leave out for the moment the musical vs. mechanical argument that is likely to crop up and just deal with speed as part of our toolkit that we can use to make music.

Physical gifts, innovation, and the musical olympics

It is important to acknowledge from the get go that we all have our physical gifts and limitations. Like it or not, there are just some guitarists who have a greater physiological capacity to synchronize their fingers with velocity. If we don’t accept this, then we are going to risk repetitive injury and certain frustration when trying to compete with those who have a natural proclivity for speed.

Accompanying physical gifts are limitations and a constant state of change in the body. Not everyone has a fully functioning set of digits. Perhaps life has thrown physical roadblocks or challenges in the way. In this case we simply have to make the best of our resources and forge ahead. Even if a guitarist exhibits virtuosic speed at some point, she might inevitably see a decline with age.

I am very grateful, however, for those many guitarists who have pushed the boundaries of speed over the years. They continually raise the bar as classical guitar technique gets refined over the decades. This allows for a more expanded musical toolkit along with all of the other advances we have observed. In general it is a great time to be a classical guitarist!

Here is an example of a guitarist, Matt Palmer, who refined his own right hand technique to incorporate AMI fingerings to great effect. In this video we can see the guitar rising to speeds that were perhaps thought impossible a few decades ago:

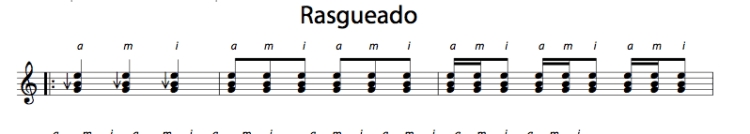

Rasgueado Flicks

Flamenco guitarists regularly exhibit speed that makes classical guitarists envious. With a closer relationship to dance and rhythm, flamenco players prioritize percussive like rhythm over tone and rubato (generally speraking). In this very rhythmic style the rasgueado technique plays a large role and constantly requires the use of extensor muscles.

Extensors are used to open up the finger joint, and flexors are used to close. As classical guitarists we are almost always dominating our movement with the flexors. Yes, our finger re-sets to its initial resting position but this happens by letting go of tension rather than activating the flexors with force.

The rasgueado technique can be very beneficial to classical players as it balances out the extensor muscles. By building up the extensors each finger can return to its neutral position faster. This results in an overall speed increase in right hand technique. Simply incorporate rasgueado flicks into your daily technical routine to develop speed in the right hand. But be mindful of building up stamina over time if this is a new technique for your body. CGC guitarists will find these in the Level 4 Technical Routines

Speed bursts

I first came across “speed bursts” in Scott Tennant’s technical tome Pumping Nylon, which will forever stand as the best cover to a classical guitar technique book.

For me, high speeds and long scales have something in similar in that they are rarely sustained for long periods of time in the classical guitar repertoire. Rather they appear in small chunks and then disappear again. There are notable exceptions to this, but for the large majority of pieces, speed will occur in small bursts.

The exercise is wonderful at building up stamina, and also teaching us to relax after each burst. Holding on to tension will hold back your speed and also tire your hands out, so it is important to incorporate active relaxation into these exercises.

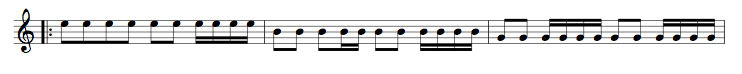

The premise is simple: play straight eighth notes (quavers) and gradually introduce longer and longer strings of sixteenth notes (semiquavers). This can be done on an open string using i,m alternation (or any other combination). If you want to add in complexity you can add in left hand notes and work on synchronizing the two hands.

Active Relaxation

In the previous point, I referred to this term “active relaxation”. It is a made up term but to me it does a good job of describing what we need to do to allow the body to function at high speed.

Adults have a lot of learned behavior that doesn’t always make sense in a musical setting. Tension is a big one that we need to deal with. Perhaps it is an instruction from the amygdala (primitive brain), but whenever we try to do something challenging we tend to tense up in anticipation and hold our breath. For fighting lions, tigers, and bears it may be useful, but not so much for playing the classical guitar.

How to develop active relaxation

To counter this naturally occurring habit, we need to actively relax. That is to say we need to make a conscious effort not to tense up and hold our breath. By doing this we are allowing our fingers to flow freely and speedily.

Breathing out while playing a fast passage with serve this purpose, and upon first try you will see just how much your body doesn’t want to do it! I suggest working on a passage with a tricky passage and choreograph a slow intake followed by a controlled outward breath just where the difficulty kicks in.

It can be a challenging request initially as it is adding more complexity into the mix, but I find that it yields good results for my students and myself.

Similarly to the choreographed breath we can be aware of opening up our body to expand our chest area. In another call to the amygdala, we tend to curl inwards with difficulty, but expanding outwards will free up our muscles. So try bringing your shoulders back and opening up your posture when passages get difficult.

After working on active relaxation in your practice session, you can refine it down to less overt actions and simply be aware of not tensing up when a faster passage arrives.

Synchronization

Although we are focusing on right hand speed, it is not just the right hand that comes into play in this discussion. The left hand has to be synchronized with the right otherwise we will hear “choppy” and unclear notes. The choppiness is a result of dead notes which are not correctly held down at the right time to match the very precise and rather unforgiving right hand pluck.

How to work on synchronization

To work on synchronization you can add in chromatic notes to the speed burst exercise above, or you can do the following type of slow practice:

To do something “slowly” does not always mean the movements are slow. In this exercise, I want you to play the notes far apart, so the beat will seem slow, but I want you to move your fingers very quickly and efficiently.

Simply take a scale, any scale, and play the notes one at a time, with four or more beats between each one. I want you to focus on your left hand fingers as you do this. As you play a note, keep the finger down and only put down the next finger at the very, very last moment. At the same time, release the previous finger by relaxing it. There is no rush whatsoever to play many notes, rather take time to watch and listen to each note as it passes and evaluate it.

- Did my left hand finger move quickly?

- Was it efficient movement?

- Did I release and relax the previous finger?

- Was the note clear and synchronized with the right hand stroke?

By honing in on this very precise synchronization you can develop an efficiency and speed that will help you play faster in your repertoire.

Two Steps forward, one step back

There is no way that you will be able to play faster if you never push your limits.

Let’s say you are working on a passage or scale and you can comfortably play it at 80 MM (that mean’s 80 beats per minute on the metronome). A realistic goal for you to find a faster “comfort” tempo might be 88 MM.

Instead of increasing the tempo notch by notch, I like to push the tempo far beyond my goal. So in this scenario, I would push the tempo in chunks past 88, perhaps up to 110. I want to reach a point where the playing really breaks down and the fingers just cannot handle the tempo cleanly. At this point start to reel the tempo back in and return to your goal tempo of 88.

Rather like parachute training for runners, I have found this process works well and results in consistent incremental gains. Furthermore, you might want to take note of where your general limit is for a piece of repertoire so that when you perform, you can start at a tempo that is slightly under what you are capable of. This will leave room for the inevitable stage fright and adrenaline to do their thing.

Rhythmic Playing

One final concept is that speed is only truly effective if it is accompanied with a solid sense of rhythm. If the fingers are moving fast, but there is no sense of rhythmic stability then, in my opinion, the speed is wasted.

Musically, it is much more exhilarating to have a strong and steady rhythmic drive than to have sloppy but fast notes. So, as with the last point, perhaps find your physical limit and then reign in the tempo a bit for performance so that you can stay in control of your rhythm.

More ideas?

These are some of the approaches that I have seen work over the years, but I know there are many more. Please contribute your practice techniques in the comments below to help other readers and members of Classical Guitar Corner.

I teally enjoyed this informative discussion about the right hand speed development. There were like ten things in various dimensions Dr Simon (he’s earning that title now) highlighted that gave me a whole new perspective and hope. Cheers!!

The video-clip you posted; surely that’s impossible!

BTW – I do enjoy your articles – they always seem to resonate with me.

Simon,

I think you make great points about countering the natural tension that occurs before trying something difficult.

To really get to the nuts and bolts of how this happens, and to learn good habits of release and relaxation while playing, I would highly recommend the Alexander Technique.

More information is here: http://www.alexandertechnique.com/musicians.htm

It’s worth reading this article in particular: http://www.alexandertechnique.com/articles/musicians/

Dear Simon,

That was very useful. Thank you. Coincidentally, I just came across an article focused on some studies by Aguado. If I understood correctly, Aguado sometimes asks us to play very fast with one finger at a time, i, for example. Is this a recognized way to improve speed and synchronization?

Thanks,

Mark

A great article once again, many thanks! Very helpful tips and considerations, sure to improve speed for any serious student. In my experience I’ve also found that working without metronome at times helps, only focusing on making each movement of the passage as fast and efficient – precise – as possible. Another helpful process is a good (20-40min) warm-up on a slow tempo, playing the notes very loud but still without any extra pressure, followed by a good stretch of the hands and fingers. Third, sleep and rest seem to play a great role at least for me: after a good rest of a day or two and good sleep speed feels much less taxing. Some right-hand fingerings seem to be a lot easier than others as well, speed-wise, so the composer’s suggestions are worth questioning. All said and done, some performances you see and hear on youtube now are still beyond comprehension – like the allegro from La Catedral up to 240 beats per minute with a perfect precision? Or Villa-Lobos Etude No.1 to 140bpm? Maybe in next life… But what gives me hope is the fact that most pieces can be played with astonishing beauty and expression across a wide variation of tempos – like with Juan Falu for instance. Speed and flashy playing do not suit all situations either, so maybe it’s just a question of working the best mix out of your (very) own capabilities and understandings and finding your own style. Wishing you all great practice and lots of motivation, and thanks again for Simon for this amazing forum!

Simon

When I took private lessons, my teacher had all his students work from The Virtuoso Guitarist by Matt Palmer. I wasn’t ready for it at the time and gave up on it. Your posting inspired me to take it off my bookshelf and give it another try.

Thank you for sharing your knowlege and insight.

Martha

Hello Simon.While listening to Matt Palmer it occurred to me that although his technique and dexterity is not in question, to me it felt ‘jumbled’ and a bit messy, am I being too picky? did the composer mean it to be played so quickly?. I would like to hear this piece played a little slower.

Thanks for your great work.

Martin

Hi Simon,

Thanks for putting all the elements of gaining speed together in one post.

my favourite in your article is the section about breathing and relaxation.

For some time already i try to apply these elements in a more relaxed approach that allows me to concentrate more on listening to the music i play.

thanks again

joannes

Hi guys,

I like this article a lot. This stuff makes sense and works for the electric as well.

I AM learning the clsssical guitar and want to take up my speed so thanks for the post Simon!!

Hi everybody

Has anyone considered to translate this great article to Dutch? Would be handy…. I would like to use it with my students in the Netherlands. Thnak you Simon!

I mean thank you Simon…..

I have two suggestions that I don’t think anyone else has suggested that I have been applying recently as I prepare for my 8th grade exam.

1. When playing a scale, play im on every note of the scale. Choose a scale you know well and a very comfortable speed but play every note im. Or for more variations every note mi, ma,am,ma,pi. It helps increase the speed in which your right hand can operate.

2. Choose a passage of music. It might just be 1 bar or it could be a phrase that goes longer. Mute the strings with your left hand and play the passage just with your right hand. With a bit of repetition you should be able to play it much faster than if you had to include the left hand and it should increase the fluency of the right hand. When you then play it with the left hand you will automatically want to play it faster as this is how you have been playing it with the right hand by itself.

Hope these suggestions make sense. The second suggestion is something everyone could try on an piece immediately. Interested to hear if it works for you.

Hi Simon,

Am going to try two steps forward etc and Immanuel, I’ll also try the two fingers on one note of a scale.

Thanks for the suggestions …

Cheers,

Bonnie

Hi Simon,

I found the breathing technique you discussed starting at 14″ particularly useful.

You continue to inspire while you educate.

I have my own opinion, perhaps a controversial one, perhaps not. Not nearly enough is said about the brain. The muscles do nothing without a command. Practice must be connected to developing the strength and complexity of a neural network. Neuroplasticity. In trying to develop a faster tremolo technique I have hit a wall at a bit more than 100 beats per minute. If I practice daily with determination I may or may not break through. If I do it will not be because my muscles changed in any way. It will be because I recruited more and more neurons into a neural network that controls my fingers. Once I have truly learned something on an instrument it is there. It might need a bit of dusting off, but basically I could leave that practising alone and do something else for a year and come back and it would still be there. Because the brain got wired, not because of muscles being stronger or changing in some way. Individual people have their own personal combination of the alleles of hundreds of genes involved in the brain, nerves and muscles and we all, unfortunately have some limitations some where in the pathway between intention and performance. Geniuses get a gift of a great combination of these gifts and then if they are discovered early and trained well, you have Yo Yo Ma or Julian Bream. But we can all use this insight into neural networks and neuroplasticity no matter what our level of talent.

I find it very hard to locate material that ties brain science to music practice, I wish someone would make a crusade of connecting what neuroscientists of learning know to what pedagogues of music at Julliard know, for the common person who want to get the most out of practicing. Realizing that a huge number of slow repetitions of any physical skill is rewiring the brain and recruiting neurons into a network and that in time it will pay off should be motivational, if people would see practice in this light!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMYQHTbPTVA

Thanks, your post is beneficial for new learners like me. I’m currently learning to play guitar and I have speed and accuracy problem especially when shifting my fingers to the next chords, this is just the reference I need!

Paco deLucia was in no way slower than pick players, au comtraire!

Very interesting article1 Thank you.

Great article. Thanks very much.

I find I use more nail and less flesh as I increase speed. Is this a good approach? I don’t want to develop the habit if it brings undesirable consequences down the track.

Any thoughts?

Thanks so much for your article. I was trying to build up my speed with no great success. In just one week using the tip about upping the metronome rate my speed and playing have both shot up beyond my wildest hopes. Thanks again.